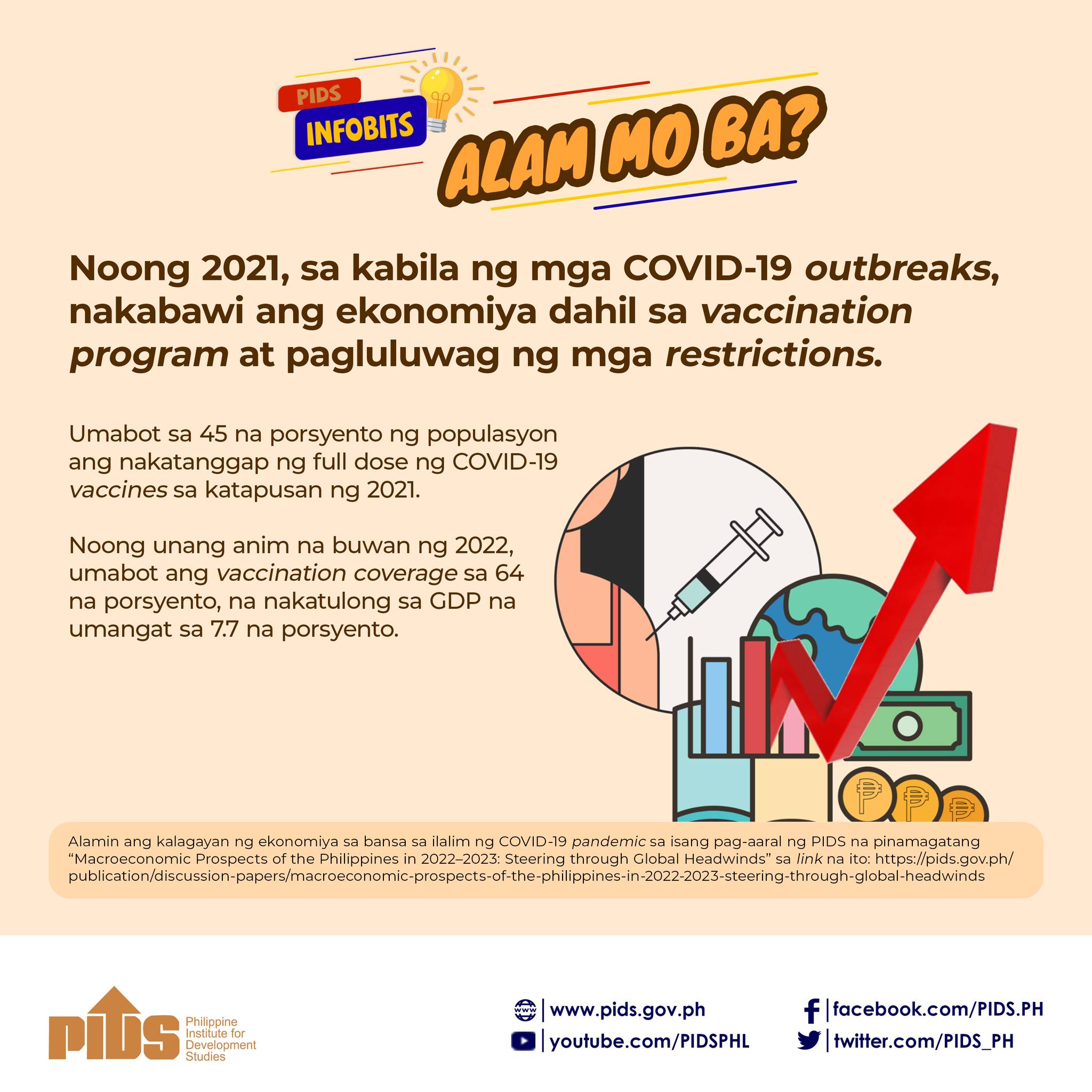

TWO potential COVID-19 vaccines are the big news these past few days. But let this not blind us to a long-standing concern yet to be addressed. A large number of Filipino children have untimely vaccination, a study of state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies revealed.

The study examined the immunization coverage and the extent of timely vaccination among children in the last 25 years, particularly from 1993 to 2017. It covered routine basic immunization — Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, Oral Polio Vaccine, Diphtheria Pertussis and Tetanus (DPT), and measles vaccines. The administration of these vaccines is part of the expanded program on immunization (EPI) in the Philippines, which is lodged under the Department of Health.

Only 10 percent of Filipino children were able to receive complete and timely immunization. Why?

Vaccination has made the most significant contribution to the prevention of infectious diseases in the past century. Through the EPI, infants and families are given access to safe and effective vaccines to protect them against common but vaccine-preventable diseases.

However, the study found out a fluctuation in the coverage of routine childhood vaccination over the last 25 years. The basic vaccination coverage in the Philippines dipped to 65 percent in 2014, the lowest level since 1990.

It must be noted that routine childhood vaccination is predominantly delivered through public facilities. About 95 percent of vaccinated children received their immunization through public health centers despite the large and increasing number of private facilities. Children of richer households or those belonging to the top 20 percent were more likely to have acquired their vaccines from private facilities while those from poorer families may have likely obtained their vaccines from public facilities. However, in general, the timeliness of administration of vaccines included in the routine basic immunization remains low regardless of socioeconomic status.

According to the study, the weak performance of the country’s EPI is caused by potential drivers, which they categorized into three — supply-related (shortages and delays), demand-related (attitudes and practices of parents and caregivers toward immunization greatly affect the coverage), and contextual factors (geographic distance, financial affordability, and cultural acceptability of immunization services).

So what could be done?

Why not shift the vaccine supply chain from a state-run supply chain management, which is proven to be highly inefficient, to innovative modalities such as private sector outsourcing?

The EPI should also consider expanding its service delivery channel to private facilities. In the Philippines, half of health facilities are privately-owned. The large network of private facilities can be used as a mechanism to rapidly expand coverage and promote timely vaccination.

Related Posts

Publications

Press Releases

Video Highlights

[No related items]