THE country’s poverty data came into question on Thursday as senators struggled to make sense of definitions and income classifications at the budget hearing of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda).

With the confusion, Acting Neda Chief Karl Kendrick T. Chua committed to discuss the matter at the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) Board, which is chaired by the Socioeconomic Planning Secretary.

Chua added that efforts to define the composition of the Philippine middle class will also be included. To date, the country does not have its own definition of which households constitute the middle class.

“What I think is the main concern, Mr. Chair, is we do not have an official definition of this. That’s why when we have certain programs and research, we come up with different numbers. So what I will do, I will discuss in the PSA Board all these to see if we can come up with something official. So moving forward, that definition will be consistent,” Chua said.

Based on the official PSA estimates, National Statistician Claire Dennis S. Mapa said the poverty threshold was estimated at P25,800 per year per Filipino or, for a family of five, P126,000 per year.

Individuals and families who earn less than this amount annually are automatically considered poor in the government’s estimates. Mapa said there are about 3 million families who are poor, consisting of around 17.67 million or close to 18 million individuals.

According to Neda Undersecretary for Planning and Policy Rosemarie G. Edillon, part of the agency’s research agenda for 2021 is to undertake a study that will help classify the non-poor.

Edillon added that the findings of the study will be presented to the PSA Board to “make it official.” She said defining and classifying the non-poor, including identifying the middle class, had been attempted by various studies in the past.

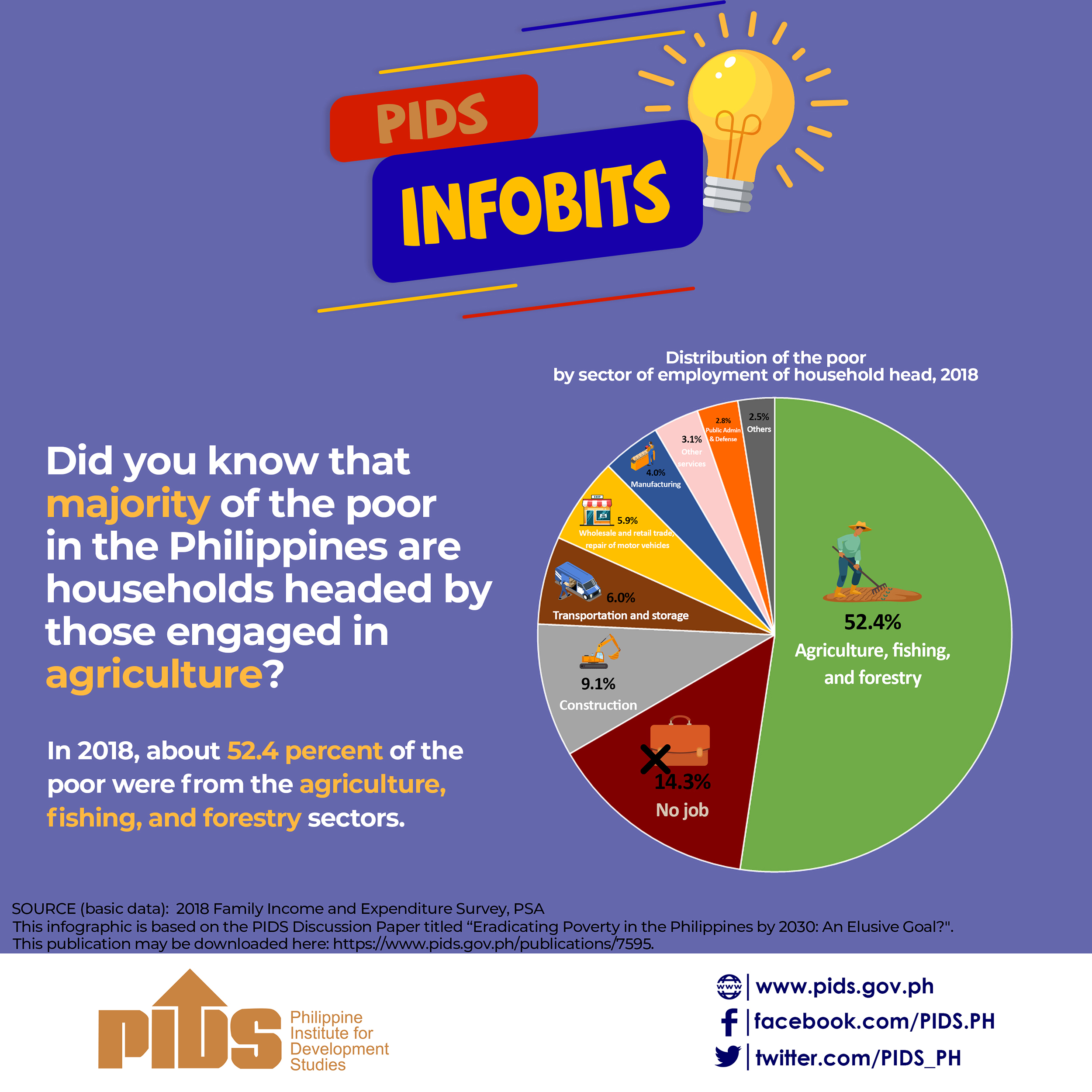

Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS) President Celia M. Reyes added that based on a recent study of the state-owned think tank, the non-poor nationwide can be classified into six groups using 2018 data.

Reyes said based on the study, the low-income but not poor group consists of 8.4 million households with a monthly family income of P10,957 to P21,914 for five; while lower middle income consists of 7.6 million families earning P21,914 to P43,828 a month.

The middle class, meanwhile, consists of 3.1 million families earning a monthly income of P43,828 to P76,699; while the upper middle income consists of 1.2 million families earning P76,699 to P131,484 a month.

Reyes said the last two classifications include the upper income but not rich group which consists of 358,000 families earning P131,484 to P290,140 per month; while the rich group consists of 143,000 families earning at least P290,140 a month.

Angara: Data gaps

However, Senate Finance Committee Chairperson Juan Edgardo Angara pointed out that the numbers do not tally given the estimates for the poor and the non-poor. Data showed that there are 26 million families nationwide and about 3 million to 4 million poor households nationwide.

This leaves about 22 million to 23 million non-poor households. However, the estimates provided by the PIDS data show only around 20.8 million by the BusinessMirror calculations, and Angara’s pegged it at 24.75 million families.

Angara recommended that the government come up with a reconciled estimate that can fit in just “one bond paper” to avoid any further confusion when it comes to the data.

“We’re just looking for better tools to understand the universe so that we can respond better. That’s the main goal, Sec. Karl,” Angara said on Thursday. “I think we can use this PIDS, at least these will be useful in terms of analyzing development in provinces. It’s relevant to Balik Probinsiya, it’s relevant to our health program, it’s relevant to our poverty programs.”

Escaping poverty

In a statement on Thursday, Chua said government interventions through the recently enacted Bayanihan Act II will help millions of Filipino families recover from poverty caused by the pandemic.

These interventions include cash-for-work programs, emergency subsidies, funds for the micro, small and medium enterprises through the banking sector.

Chua said that in terms of getting back on track to reducing poverty incidence in the country, the pace will also depend on when the vaccine will be available, so that the economy can fully open.

“Right now we are seeing a gradual recovery of the economy and employment has bounced back significantly. There’s a lot of uncertainty but the general direction is that we are going to see more opening up of the economy and we are going to make sure that people who are not able to work will be supported,” he said.

Recovery and the kind of jobs that will be available, he added, will mostly depend on personal behavior and the people’s ability to practice minimum health standards.

The Neda chief earlier said there could be a temporary increase in urban poverty because of the pandemic and quarantine in urban areas, but a gradual recovery of the economy can be achieved so long as the economy can safely open up.

Chua said the pandemic has significantly affected urban areas such as Metro Manila and Cebu because of the higher number of Covid-19 cases in these areas. These economic centers experienced longer lockdowns that prevented millions from working, causing them to slip back or fall deeper into poverty.

“This indicates that the impact on the rural areas is minimal, if at all. So, we are going to make sure that the urban poor and those affected by the quarantines will get the support that they need to prevent further deterioration,” Chua said.

Chua said prior to the pandemic, around 6 million were lifted from poverty in 2018, four years ahead of the 2022 target. As of 2018, the poverty rate has gone down from 23.5 percent in 2015 to 16.7 percent in 2018.

Who’s truly poor in PHL? Confused senators ask Neda experts to clarify