“There really is such a thing as society,” said the Covid-stricken UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson during his medical isolation. After his ICU recovery, Johnson thanked profusely the UK’s community of health workers and told the larger British society—repeatedly—that, “we are going to do it together.”

Johnson’s stance contradicts his Conservative predecessor, Margaret Thatcher, who told the world that “There is no such thing as society.” In the 1980s, Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan led the global promotion of the economic philosophy of “rugged individualism” in a laissez faire policy environment. Under the Thatcher-Reagan privatization framework, governments have no business providing public services. Let the private sector take over the public utilities engaged in the delivery of public services such as transport, water, medical, power, communications, and so on.

Today, the world is rediscovering the central and strategic importance of having a strong government that is able to persuade (sometimes command) the population to observe the virus containment protocols while mobilizing resources to combat the virus spread, rebuild broken public health system and infras, and provide the people, the poor in particular, the means to survive any economic lockdown. All in the name of the common good. All in the name of a collectivity called society.

In a pandemic, no man or woman is an island. A contagious virus does not distinguish whether one lives in a gated village or a congested community of informal settlers. Nor does the virus respect national borders. The rich and the poor, the developed and developing countries are all vulnerable. Clearly, the health of one depends on the health of all. Els Hertogen, the director of a Belgian agency, summed it up neatly: “In the global battle against corona, we are only as strong as our weakest link.”

But the problem is that the weakest link is not sufficiently being strengthened in Covid times. The needs of the most vulnerable are often addressed in a limited, stop-gap and ad-hoc manner. This is especially true in the developing economies.

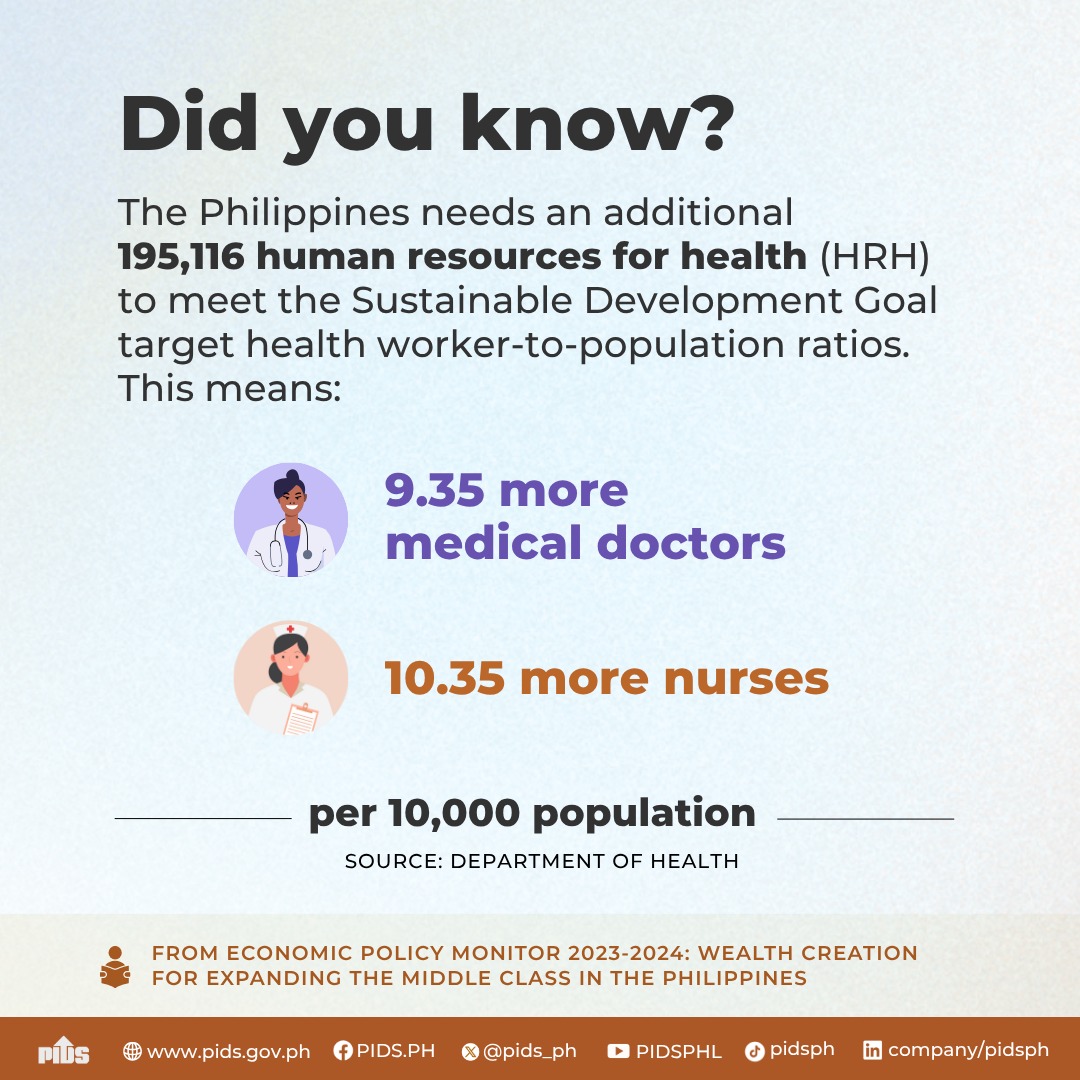

There are huge gaps in the delivery of health and social protection for the poor. First, the public health system is either underdeveloped or broken due to underfunding, official neglect and the obsession of some officials to privatize health and public services. Second, there is no well-functioning public distribution system in the delivery of essential goods during emergency health situations. This is vividly illustrated in the inability of vegetable farmers in Northern and Southern Luzon to deliver their fresh produce to Metro Manila, whose poor inhabitants are being fed mostly with rice, canned sardines and cheap noodles.

Third, budget-strapped governments cannot make up their minds on whether to give full, partial or selective social protection assistance to the poor such as food packages and replacement incomes during the quarantine periods. Fourth and relatedly, they cannot also decide whether to cover all or select groups of the poor and needy.

The last issue—universal or select/targeted coverage for social assistance—has become a battleground in the Philippines. Some Metro Manila mayors complain that the Department of Social Welfare and Development has been excluding so many poor households in the list of beneficiaries because the DSWD is using an outdated 2015 Census and an error-prone list of CCT families. Mayor Rex Gatchalian of Valenzuela gave one reason for the huge gap in the DSWD list of poor households and the actual count by the local government units—the noninclusion in the DSWD list of migrant families, particularly those renting single rooms or occupying informally built dwellings.

Very often, these migrant families, along with the domestic workers and street dwellers, do not bother to formally register with the barangays. And yet, these workers are among the poorest of the poor.

On the other hand, there is the complaint by some local government officials on how the so-called middle class families are also being impoverished by the pandemic and yet are not receiving any assistance from the government.

The trouble is that there is no established definition of what is a “middle class.” First, there is the assumption by some economists that those above the poverty line are nonpoor and, therefore, belong to the middle class. However, the poverty line is set at a ridiculously low level—around P70 per person a day in the first semester of 2018, resulting in a poverty incidence rate of just over 16 percent for the country. If this threshold is raised to a more realistic level, at about twice or thrice P70, the poverty rate easily shoots up to 50 percent or so, which is close to the self-rated poverty figure given by the Social Weather Station.

National Economic and Development Authority itself has difficulty establishing the size of the middle class. Neda’s Philippine Institute of Development Studies estimates that 40 percent of the country’s population belong to the middle-income class, while majority or 58 percent belong to the lower-income class. In a PIDS study, the poor and low-income earn up to P18,200 a month, the “middle income” (low, middle and upper) between P18,200 and P109,200, the “upper income” between P109,200 and P180,000, and the rich between P180,000 and above. The last earns at least 20 times over the poverty line.

But here comes Neda’s Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, a blueprint that tries to promote the vision of a developed Philippines, one that is prosperous and “predominantly middle class society” by 2040. It gave the following indicators of a middle-class family: home ownership, steady source of income, college education for the children, a motor vehicle, stable finances to meet daily needs and all contingencies, savings for retirement, and time for travel and vacation. Estimated income of a middle-class family? P120,000 monthly based on 2015 prices!

Clearly, the poor and the near poor constitute the overwhelming majority, at least more than 80 percent of the total population. The poor listed by the DSWD, the excluded poor (mostly migrant families and those unregistered with the barangays) and the so-called nonpoor who earn below the minimum P120,000 a month all deserve social protection assistance in Covid times.

In this connection, the proposal of the Social Watch Philippines is worth heeding. Like many concerned CSOs, the SWP is worried over the delay in the delivery of urgent assistance (cash and noncash) to the poor. The government’s Social Amelioration Program has targeted 18 million families (roughly equal to 75 percent of the estimated total of 24 million families in the country. The SWP argues that assistance to “all those living in impoverished or low-income communities” should be universalized, meaning there is no need to conduct the bureaucratic, time-consuming and error-prone means of testing and validation processes just for the purpose of coming with a list of the included and excluded.

As to the poor in upscale neighborhoods and gray areas, e.g., hidden alleys in rich subdivisions and cemeteries converted into homes of the homeless, special targeting and listing operations can be done by the DSWD and LGUs.

To SWP, a more universal and inclusive approach in social protection delivery reduces errors in the listing of the poor and vulnerable, minimizes patronage politics and “palakasan” in the listing of beneficiaries, and prevents social unrest. And yes, such an approach promotes social cohesion and solidarity. To repeat what Els Hertogen said, we can only be as strong as the weakest link.

Johnson’s stance contradicts his Conservative predecessor, Margaret Thatcher, who told the world that “There is no such thing as society.” In the 1980s, Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan led the global promotion of the economic philosophy of “rugged individualism” in a laissez faire policy environment. Under the Thatcher-Reagan privatization framework, governments have no business providing public services. Let the private sector take over the public utilities engaged in the delivery of public services such as transport, water, medical, power, communications, and so on.

Today, the world is rediscovering the central and strategic importance of having a strong government that is able to persuade (sometimes command) the population to observe the virus containment protocols while mobilizing resources to combat the virus spread, rebuild broken public health system and infras, and provide the people, the poor in particular, the means to survive any economic lockdown. All in the name of the common good. All in the name of a collectivity called society.

In a pandemic, no man or woman is an island. A contagious virus does not distinguish whether one lives in a gated village or a congested community of informal settlers. Nor does the virus respect national borders. The rich and the poor, the developed and developing countries are all vulnerable. Clearly, the health of one depends on the health of all. Els Hertogen, the director of a Belgian agency, summed it up neatly: “In the global battle against corona, we are only as strong as our weakest link.”

But the problem is that the weakest link is not sufficiently being strengthened in Covid times. The needs of the most vulnerable are often addressed in a limited, stop-gap and ad-hoc manner. This is especially true in the developing economies.

There are huge gaps in the delivery of health and social protection for the poor. First, the public health system is either underdeveloped or broken due to underfunding, official neglect and the obsession of some officials to privatize health and public services. Second, there is no well-functioning public distribution system in the delivery of essential goods during emergency health situations. This is vividly illustrated in the inability of vegetable farmers in Northern and Southern Luzon to deliver their fresh produce to Metro Manila, whose poor inhabitants are being fed mostly with rice, canned sardines and cheap noodles.

Third, budget-strapped governments cannot make up their minds on whether to give full, partial or selective social protection assistance to the poor such as food packages and replacement incomes during the quarantine periods. Fourth and relatedly, they cannot also decide whether to cover all or select groups of the poor and needy.

The last issue—universal or select/targeted coverage for social assistance—has become a battleground in the Philippines. Some Metro Manila mayors complain that the Department of Social Welfare and Development has been excluding so many poor households in the list of beneficiaries because the DSWD is using an outdated 2015 Census and an error-prone list of CCT families. Mayor Rex Gatchalian of Valenzuela gave one reason for the huge gap in the DSWD list of poor households and the actual count by the local government units—the noninclusion in the DSWD list of migrant families, particularly those renting single rooms or occupying informally built dwellings.

Very often, these migrant families, along with the domestic workers and street dwellers, do not bother to formally register with the barangays. And yet, these workers are among the poorest of the poor.

On the other hand, there is the complaint by some local government officials on how the so-called middle class families are also being impoverished by the pandemic and yet are not receiving any assistance from the government.

The trouble is that there is no established definition of what is a “middle class.” First, there is the assumption by some economists that those above the poverty line are nonpoor and, therefore, belong to the middle class. However, the poverty line is set at a ridiculously low level—around P70 per person a day in the first semester of 2018, resulting in a poverty incidence rate of just over 16 percent for the country. If this threshold is raised to a more realistic level, at about twice or thrice P70, the poverty rate easily shoots up to 50 percent or so, which is close to the self-rated poverty figure given by the Social Weather Station.

National Economic and Development Authority itself has difficulty establishing the size of the middle class. Neda’s Philippine Institute of Development Studies estimates that 40 percent of the country’s population belong to the middle-income class, while majority or 58 percent belong to the lower-income class. In a PIDS study, the poor and low-income earn up to P18,200 a month, the “middle income” (low, middle and upper) between P18,200 and P109,200, the “upper income” between P109,200 and P180,000, and the rich between P180,000 and above. The last earns at least 20 times over the poverty line.

But here comes Neda’s Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, a blueprint that tries to promote the vision of a developed Philippines, one that is prosperous and “predominantly middle class society” by 2040. It gave the following indicators of a middle-class family: home ownership, steady source of income, college education for the children, a motor vehicle, stable finances to meet daily needs and all contingencies, savings for retirement, and time for travel and vacation. Estimated income of a middle-class family? P120,000 monthly based on 2015 prices!

Clearly, the poor and the near poor constitute the overwhelming majority, at least more than 80 percent of the total population. The poor listed by the DSWD, the excluded poor (mostly migrant families and those unregistered with the barangays) and the so-called nonpoor who earn below the minimum P120,000 a month all deserve social protection assistance in Covid times.

In this connection, the proposal of the Social Watch Philippines is worth heeding. Like many concerned CSOs, the SWP is worried over the delay in the delivery of urgent assistance (cash and noncash) to the poor. The government’s Social Amelioration Program has targeted 18 million families (roughly equal to 75 percent of the estimated total of 24 million families in the country. The SWP argues that assistance to “all those living in impoverished or low-income communities” should be universalized, meaning there is no need to conduct the bureaucratic, time-consuming and error-prone means of testing and validation processes just for the purpose of coming with a list of the included and excluded.

As to the poor in upscale neighborhoods and gray areas, e.g., hidden alleys in rich subdivisions and cemeteries converted into homes of the homeless, special targeting and listing operations can be done by the DSWD and LGUs.

To SWP, a more universal and inclusive approach in social protection delivery reduces errors in the listing of the poor and vulnerable, minimizes patronage politics and “palakasan” in the listing of beneficiaries, and prevents social unrest. And yes, such an approach promotes social cohesion and solidarity. To repeat what Els Hertogen said, we can only be as strong as the weakest link.