In terms of education, advocates of gender equality in the Philippines should also pay attention to enhancing boys' wellbeing, without compromising girls' educational progress.

In his presentation at a forum conducted by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), economist Vicente Paqueo lauded the country's progress in reducing gender gaps. However, he was also quick to point out that boys are now lagging behind girls in human capital development.

"Gender equality means that human beings are equal in the eyes of the law and in practice regardless of their gender. Historically, however, the fight for gender equality has been focused on raising the status of females toward equality with males," he explained.

Given this focus on girls, Paqueo maintained that gender advocacy has benignly neglected boys. Showing data from the Philippine Statistics Authority and the Department of Education, he noted that boys have been lagging behind girls in almost all measures of education performance—from dropout rates to graduation rates to achievement test scores.

A related PIDS study on "Boys Are Still Left Behind in Basic Education" found that compared to girls, boys drop out at higher rates, are less likely to graduate on time, and eventually, are less likely to get a college degree.

According to this study, about two in every three out-of-school children (OOSC) aged 5–15 years in 2017 were boys; three out of four were from the poorest households. The gender gap in OOSC also widened as age progresses, with boys twice as likely to drop out of high school than girls.

The PIDS study showed that the gender gap in OOSC was widest in senior high school, where 22 percent of boys did not reach the expected level compared with only 12 percent of girls. In junior high school, OOSC rate for boys was at 8 percent compared to 3 percent for girls.

Paqueo enumerated a number of possible reasons why boys are less motivated than girls to attend and perform better in school. Poverty pressures, he said, were among them as more males drop out of school earlier for work to augment household income.

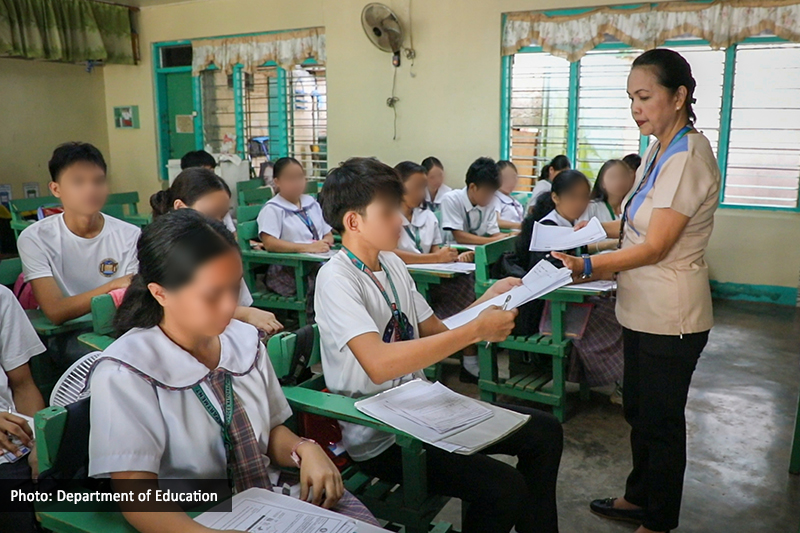

He likewise noted that the rate of return to education is higher for women than for men. Thus, parents from poor households are inclined to invest more in girls’ education. “School environment is biased against boys, with girls seated in front and boys at the back. Having more female teachers also affect the motivation of boys to perform better,” he added.

He suggested that more studies should be done on factors such as households, teachers, and school attitudes, as well as other social norms and practices, which contribute to boys’ lagging behind girls in education.

In particular, he pointed to the need to investigate further the effects of female teacher dominance in Filipino classrooms and other aspects of school and class environment on boys’ education performance. Given the higher opportunity cost for schooling among boys than girls, he recommended the possibility of giving bigger conditional grant amount for boys under the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, the Philippine government’s conditional cash transfer program.

Helping disadvantaged boys catch up with girls in education is a fair application of the gender equality principle, according to Paqueo.

"Helping boys catch up with girls in basic education should be anchored on a win-win strategy—something that does not only raise the poor performance of both girls and boys in school but also help boys draw level with girls," he stressed. He warned that "failure to pursue strategies that address gender biases that are hurtful to either boys or girls means reduced economic returns to human capital investment."###

In his presentation at a forum conducted by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), economist Vicente Paqueo lauded the country's progress in reducing gender gaps. However, he was also quick to point out that boys are now lagging behind girls in human capital development.

"Gender equality means that human beings are equal in the eyes of the law and in practice regardless of their gender. Historically, however, the fight for gender equality has been focused on raising the status of females toward equality with males," he explained.

Given this focus on girls, Paqueo maintained that gender advocacy has benignly neglected boys. Showing data from the Philippine Statistics Authority and the Department of Education, he noted that boys have been lagging behind girls in almost all measures of education performance—from dropout rates to graduation rates to achievement test scores.

A related PIDS study on "Boys Are Still Left Behind in Basic Education" found that compared to girls, boys drop out at higher rates, are less likely to graduate on time, and eventually, are less likely to get a college degree.

According to this study, about two in every three out-of-school children (OOSC) aged 5–15 years in 2017 were boys; three out of four were from the poorest households. The gender gap in OOSC also widened as age progresses, with boys twice as likely to drop out of high school than girls.

The PIDS study showed that the gender gap in OOSC was widest in senior high school, where 22 percent of boys did not reach the expected level compared with only 12 percent of girls. In junior high school, OOSC rate for boys was at 8 percent compared to 3 percent for girls.

Paqueo enumerated a number of possible reasons why boys are less motivated than girls to attend and perform better in school. Poverty pressures, he said, were among them as more males drop out of school earlier for work to augment household income.

He likewise noted that the rate of return to education is higher for women than for men. Thus, parents from poor households are inclined to invest more in girls’ education. “School environment is biased against boys, with girls seated in front and boys at the back. Having more female teachers also affect the motivation of boys to perform better,” he added.

He suggested that more studies should be done on factors such as households, teachers, and school attitudes, as well as other social norms and practices, which contribute to boys’ lagging behind girls in education.

In particular, he pointed to the need to investigate further the effects of female teacher dominance in Filipino classrooms and other aspects of school and class environment on boys’ education performance. Given the higher opportunity cost for schooling among boys than girls, he recommended the possibility of giving bigger conditional grant amount for boys under the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, the Philippine government’s conditional cash transfer program.

Helping disadvantaged boys catch up with girls in education is a fair application of the gender equality principle, according to Paqueo.

"Helping boys catch up with girls in basic education should be anchored on a win-win strategy—something that does not only raise the poor performance of both girls and boys in school but also help boys draw level with girls," he stressed. He warned that "failure to pursue strategies that address gender biases that are hurtful to either boys or girls means reduced economic returns to human capital investment."###