THE level of health spending in response to Covid-19 should be maintained and used as a new base in the coming years to continue the reduction in Filipinos’ out-of-pocket expenses for their medical needs, according to an expert from the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

In a presentation at the Development Policy Research Month (DPRM) forum of the Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS), ADB Southeast Asia Principal Health Specialist Eduardo P. Banzon said government health spending saw a “dramatic increase” to 28 percent in 2020.

While public spending on health has been rising since 2016, the rate of increase has never breached 20 percent. Prior to the rate of increase in 2020, the public health spending posted the highest increase in 2018 at 18 percent.

“So part of the challenge that we have to do now is to make sure that this increase in spending that the government has provided for health should not go down. And really, it should become sort of a new base,” Banzon said.

The significant increase in health spending in 2020, Banzon said, could explain the slowdown in the increase in Household Out of Pocket (OOP) Expenditure to 3.6 percent in 2020.

Prior to 2020, based on the Current Health Expenditures (CHE) data released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), OOP grew 6 percent in 2019; 6.3 percent in 2018; and 7.9 percent in 2017.

Based on the data, Banzon noted, CHE posted a 12.6-percent increase to P895.88 billion in 2020. He noted that this was also the fastest growth since 2014.

Given this, the composition of the CHE in 2020 was 45.7 percent accounted for by government schemes and compulsory contributory health care financing schemes and 44.7 percent OOP.

The remaining 9.6 percent was composed of voluntary health-care payment schemes such as health maintenance organization (HMO) and health insurance.

“If the government spends more money for health using tax revenues, using compulsory contributions, that might

actually trigger further reduction in out of pocket [health] expenditures,” Banzon said.

Financing options

Banzon noted that there are many financing opportunities that could finance the country’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) which will help reduce OOP.

These include sin tax collections from the sale and consumption of tobacco, alcoholic beverages, and sweetened beverages and the national government share in the revenues of the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (Pagcor).

Banzon noted that the government also receives a 40-percent share from the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) which is also being used to improve the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth).

There is a need to track these taxes and funds as well as ensure the timely release and transfers for the UHC. It is estimated that Pagcor revenue shares for health will increase to P17.78 billion while PCSO shares could reach P1.35 billion by 2026.

Apart from these, Banzon recommended that increasing the annual appropriations of the DOH in the National Budget would help as well as local government efforts in engaging the private sector through Public Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Lived experiences

Increasing the spending for health is necessary given the hardships Filipino families face, especially in terms of “catastrophic health expenditures” which are greater than or equal to 40 percent of a household’s capacity to pay.

In a study, Ateneo de Manila University Development Studies Program Research Associate Vincen Gregory Yu said the health financing experiences of ordinary Filipinos can be summed up in 4 “Ps”—pagtitiis, pangungutang, pagmamakaawa and PhilHealth.

Pagtitiis, which means enduring symptoms of health conditions, involves refusing to seek treatment and resorting to self-medication. Filipinos would also turn to alternative or traditional medicine.

Yu said their Focus Group Discussion (FGD) participants said not seeking medical attention was the “rational” thing to do since money is often lacking. Funds that could go to health expenses are instead used to pay off debts.

For Filipinos, pangungutang or borrowing money, often becomes their first resort in addressing their medical needs. Unfortunately, Yu said, this “often leads to more catastrophes.”

The third “P” is pagmamakaawa which refers to the process of soliciting help from state and private institutions and individuals. This often happens as a last resort when no friend or family can lend them money.

Yu said this is a process in itself since it requires submitting documents, traveling, and assigning healthy family members to solicit from various institutions and individuals.

Often, pagmamakaawa means turning to patronage politics as well as employing their social capital in order to obtain the needed amount.

“Paying for health care is literally a laborious process. Labor is not just physical; it is also emotional,” Yu said. “Social relationships are crucial [and that]obtaining help does not equate to sufficient help.”

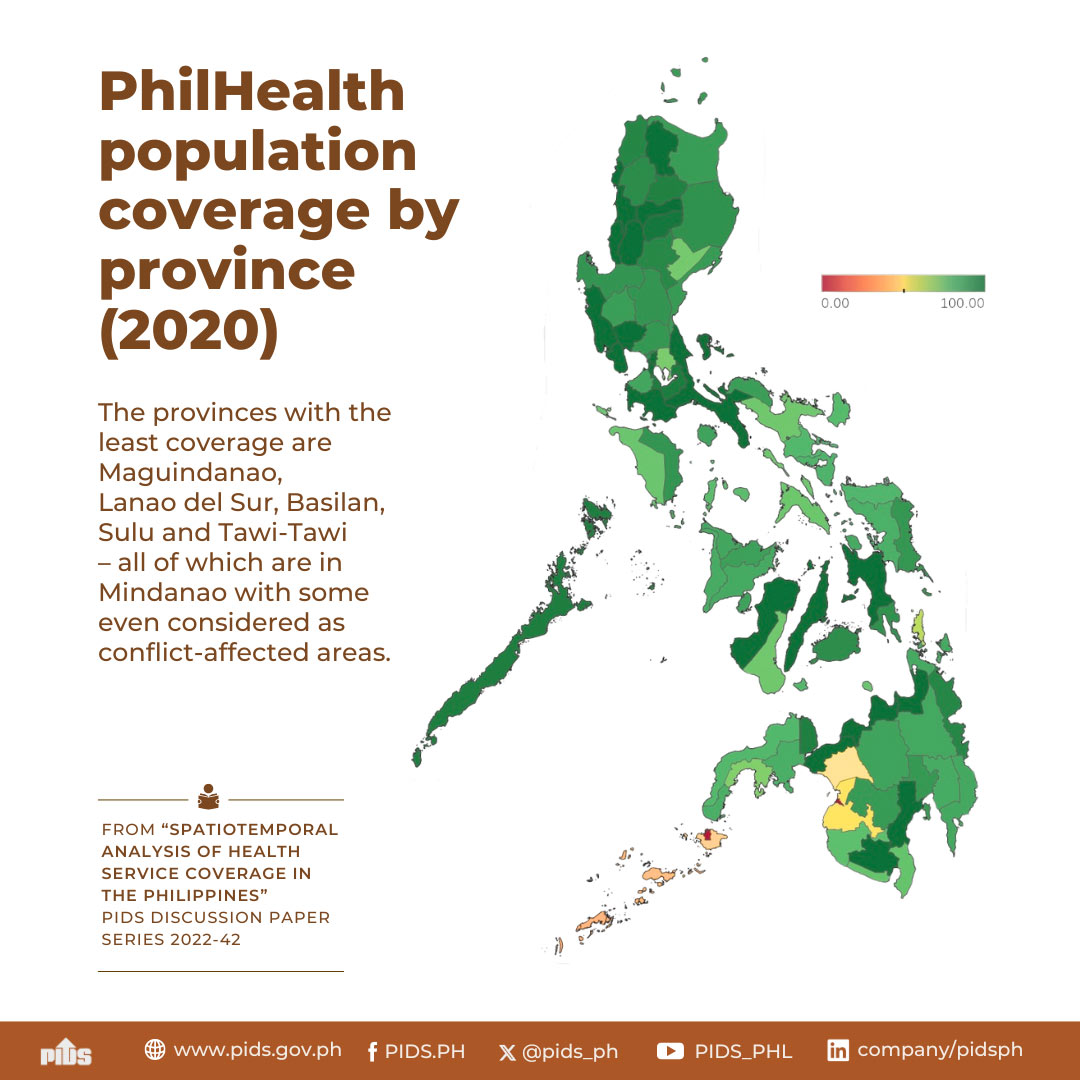

PhilHealth is the last “P” in health financing. This is accessed only when Filipinos are already hospitalized.

However, Yu said, many poor Filipinos consider their poverty as a barrier in accessing PhilHealth. This indicates that not all Filipinos are aware of how PhilHealth works and that its operations are often shrouded in “varying misconceptions.”