LAST April I marked my 23rd year as a development economist in the realm of public policy, administration, and governance, the second part of my professional track, which began in 1988 as a government economic planner for nine years. This makes me a 32-year-old development worker! The first half of these 23 years was devoted to work on climate change mitigation, environmental management and energy sector reforms, and the next half, I had branched out into infrastructure development reforms and program management. It has been a fulfilling professional run, being part of several medium-term projects, which aimed to support the Philippine government in introducing transformative reforms — whether in the form of policies, laws, rules, or plans and programs — and which are crucial to improving the country's competitiveness and investment climate — all invariably leading to a better Philippines.

I refer to my professional experiences as real-life testimonial of a development worker in the "business of reforms." In all the projects I had served, I realized that my learnings as a student of economics and public administration were neatly put to good use in advocating for reforms. The systematic, analytical and objective approach to problem-solving coupled with cognizance of social participation in introducing and sustaining reforms, where needed, are undeniably the best takeaway, which made working in reform-oriented development projects all worthwhile for me. The "marketing of reforms," from the perspective of an economist who doesn't want to be stuck in the analytical armchair black hole, is the sexier version of being a reform agent. In my lifetime-to-date as a reform agent, I have participated, albeit in invisible supporting roles, in the passage of landmark reforms that have now become part of our ongoing economic life in both national and local levels. I believe strongly that reforms can only lead to better results when diagnosed and designed well, and executed efficiently and consistently.

When it comes to appreciating the role of regulatory reforms in the country's national life, I thank two brilliant economists-public policy experts, who I have so fortunately worked with and learned from, including my current affiliation, the Regulatory Reforms Support Program for National Development (Respond): Dr. Enrico Basilio, foremost Philippine transport and logistics expert and a professor at the UP National Center for Public Administration and Governance, and Dr. Gilbert Llanto, former president of the government think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies and former undersecretary at the National Economic and Development Authority. Dr. Basilio leads Respond and Dr. Llanto is our team leader on regulatory effectiveness. I share the thoughts below, which are enriched by the deep knowledge and insights of these two colleagues.

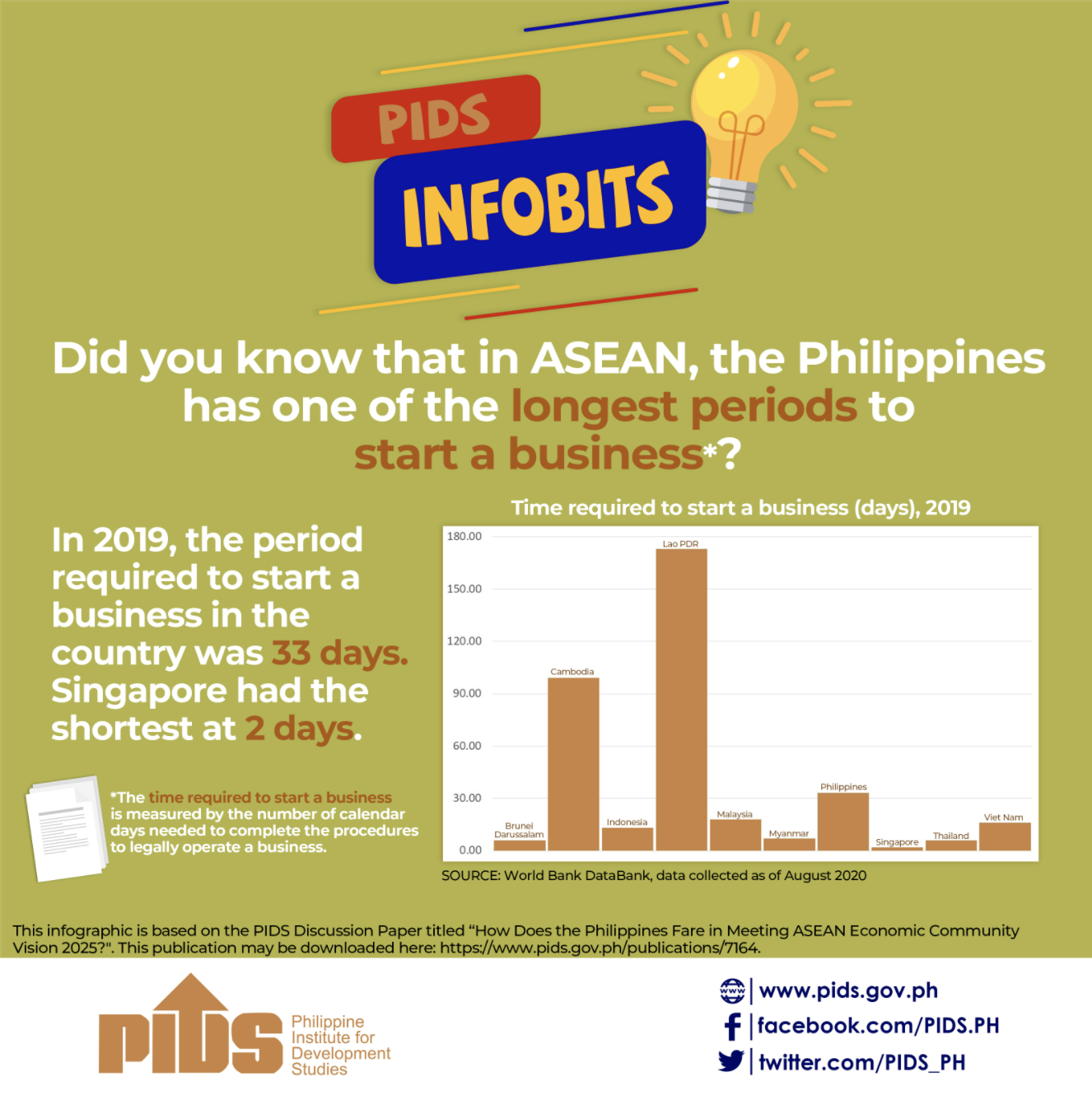

The value of regulations. Aside from formulating and implementing sound policies that are conducive to the growth and development of the economy, equally important is a stable regulatory environment, which promotes competition and reduces barriers to investments. Bad regulations increase the cost of doing business and these ultimately spill over as a burden to consumers in terms of higher prices or unavailability of goods and services. The backlash is that bad regulation also adversely affects producers, who deal with production losses and the overall economy, in terms of lost jobs and income opportunities. In order to pave the way for economic progress to flow smoothly, regulations are important in setting the right signals and directions.

Barriers in instituting reforms. Mindset is a key deterrent to be overcome, especially among bureaucrats and legislators, who may be well-meaning but are stuck in the archaic thinking that regulation is about command and control or the conflicted regulators, who prefer the preservation of the status quo given the commercial benefits they derive in using their regulatory powers. These are realities to be confronted in a governance system that has been attuned to the subverted idea that democracy works for everyone but better for some perhaps, as the protection of entrenched commercial interests become priority over the larger public welfare. It's a classic case of market imperfection when government, in its role as guardian of the balance of commercial and public interests, becomes a captive and biased protector of the well-denominated side. In this case, the regulators and policy makers become the unwilling participants in the reform process. They are vilified in the public's eye no doubt and, in the process, bring down the entire government as the uncaring purveyor of public misery, the perpetrators of corruption.

This is probably the single biggest challenge that needs to be quickly dispelled at the start of any reform initiative. At the opposite end of the tunnel is the classic lack of understanding among the "regulated sectors" that good regulations enhance market efficiency. Regulations are rules of the game that constrain or enhance the behavior of economic agents; these need to be well understood and accepted.

Facilitators of success. Some of the key factors that portend success in advocating transformational reforms are: the identification of a "regulatory reform champion/s" in the public (legislature and bureaucracy) and private sectors to consistently lead in the discussion-to-implementation loop of reform initiatives; continuing advocacy and coalition building by well-meaning stakeholders who have a larger view of how the "spoils of reforms," i.e., producer and consumer surpluses in economic parlance, can be shared equitably, to push a reform agenda and neutralize unwilling regulators; and peer pressure via awareness of how similarly situated or the leading countries are doing it and how we are faring by benchmarking against their indicators of performance.

The above are by no means a cure-all prescription of pushing for transformational reforms. But I think that many in the circle of development advocacy can also attest to similarity in experience and lessons learned. I am a believer of potential, in all areas and all players. No discrimination anywhere, and for as long as I can remember, I have been taught well in the "school of inclusivity" and perceptive thinking. There are no bad inputs, just bad decisions and bad repercussions. Same principle in regulatory reforms advocacy — we listen to and learn from all, then we find our way in the mess or maze, guided by the singular goal of promoting what works best for all sides with least adversarial results. Transformation reforms are good pills for the economy.