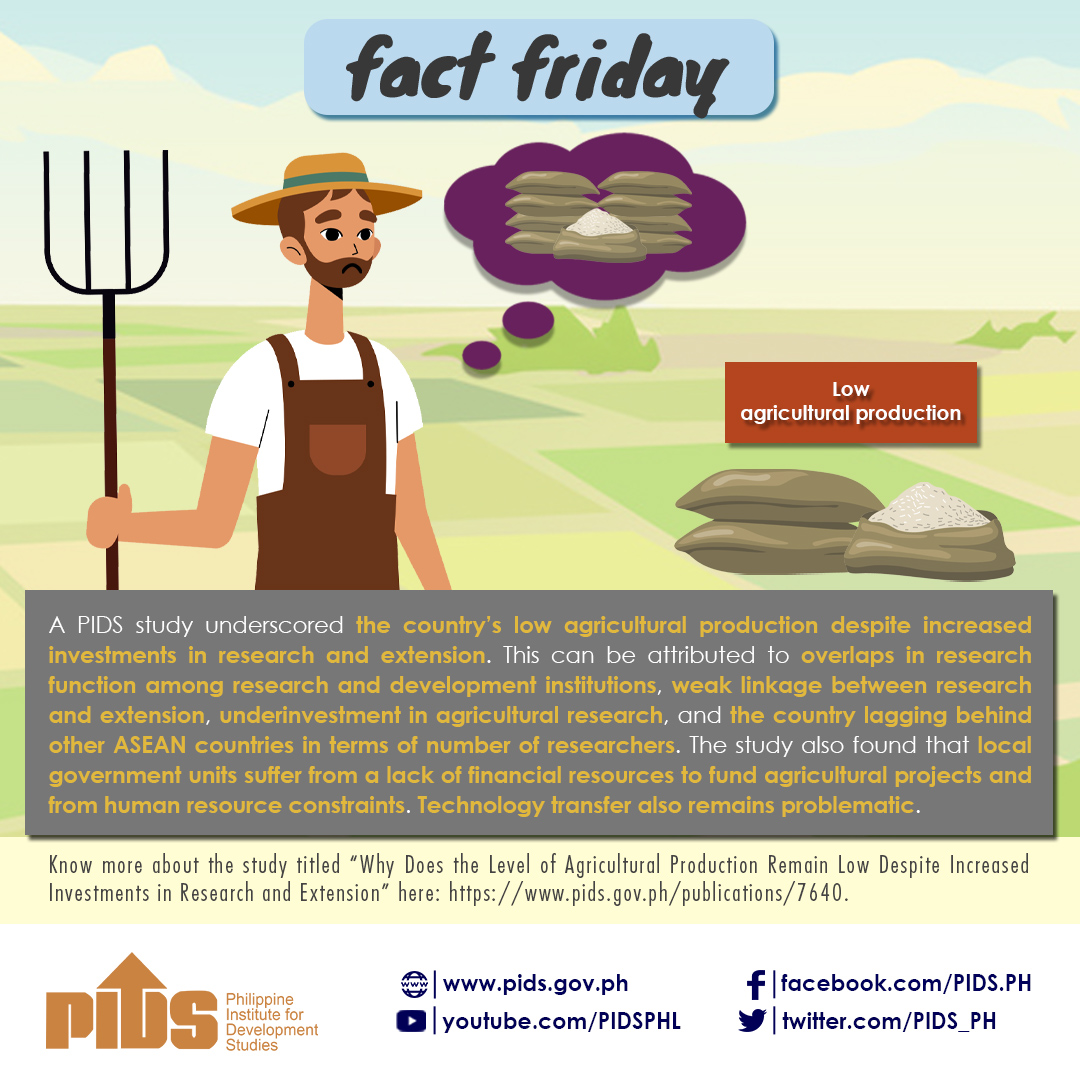

THE Philippines’s self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) in rice fell to 77 percent in 2022, the lowest in more than two decades, as the country remained as one of the world’s largest importers of the staple.

Latest data released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) showed that the country’s rice SSR last year was lower than the 81.5 percent level recorded in 2021.

Historical PSA data showed that last year’s rice SSR was the lowest in 24 years or since 1998, when it settled at 72.1 percent. This is the third time, since 1988, that the country’s rice SSR was below 80 percent.

The PSA defines SSR as the extent to which the country’s domestic production can meet its domestic requirement.

“A ratio of less than 100 percent indicates inadequacy of food production to cope with the demand of the population,” the PSA said. “The higher the ratio, the greater the self-sufficiency.”

Danilo V. Fausto, President of the Philippine Chamber of Agriculture and Food Inc. (PCAFI), said the country’s latest rice SSR figure is “very disheartening.”

“We are struggling very hard to increase our production, our sufficiency and productivity. We are pushed back by recommendations that give incentives to importers than to producers,” Fausto told the BusinessMirror in an interview.

“If these tariff reductions push through, we can expect that our self-sufficiency would not just be 77 percent but will be below the passing grade of 75 percent. Hindi lang tayo bagsak, kung hindi repeater na,” he added.

The country’s milled rice output last year fell slightly to 12.921 million metric tons (MMT) from the record-level of 13.054 MMT registered in 2021, according to the PSA.

During the same year, the Philippines’s rice imports surged to a record 3.863 MMT, about 30 percent higher than the 2.967 MMT it imported in 2021, PSA data showed. With such volume, the Philippines remained as the world’s second-biggest buyer of rice behind China, which imported 6.155 MMT of rice last year.

‘Check the formula’

However, Agriculture Undersecretary for Rice Industry Development Leocadio S. Sebastian said it is important to check the formula used by the PSA in calculating the rice SSR.

Sebastian pointed out that the PSA’s formula takes into account importation as part of the country’s overall supply base and does not consider the local demand in a given year.

The PSA’s formula for SSR in any commodity is as follows: local production divided by the total supply (production plus imports minus exports) multiplied by 100 percent.

“Hence, if you have more rice imports, the rice sufficiency will go down. The formula is not local production minus exports divided by local demand,” Sebastian told the BusinessMirror.

Pundits, including former agriculture secretaries, and industry stakeholders have criticized the PSA’s SSR formula in the past, arguing that it does not provide a “more realistic picture” of the country’s rice supply situation.

They said that as long as the Philippines imports rice, then its SSR will never hit 100 percent, since, mathematically speaking, imports form part of the denominator of the formula.

PSA standards

However, Sebastian noted that the PSA is following “certain standards” that is why it uses such a formula for calculating the SSR. The PSA adopted the Food and Agriculture Organization’s formula and definition for SSR.

“As such we should be aware of their formula, considering that rice importation is liberalized which means, our imports are not just determined by our deficit but also by local and international market situation,” Sebastian said.

He disclosed that the agriculture department is using an alternative formula that measures the level of rice supply in relation to the country’s demand to “monitor” how the country is “progressing in terms of sufficiency level.”

Using this alternative formula, Sebastian answered in the affirmative when asked if the country’s rice SSR last year was higher than 77 percent.

Impact of climate change

Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU) economist Leonardo Lanzona told the BusinessMirror that if an SSR of 77 percent is the best the country can do, it is fair for the country to consider importing the rest of the Philippines’s needs for the staple.

“We don’t want to be placed in a situation where the costs are much greater [than the] benefits obtained from trying to reach self-sufficiency. If 77 percent is [the] best we can do, without incurring too much cost, then the rest can be imported,” Lanzona said.

“We need to consider all of the sectors, making sure that the net benefits in various agricultural outputs are maximized given the constraints that we face,” he added.

The decline in the SSR, Lanzona said, may have been caused by climate change and other “uncontrollable factors.” This may also reflect the lack of efficiency in the current administration.

“The ratio should be the least of our concerns. The important thing is [to] assess the benefits from raising the ratio in relation to their costs,” Lanzona said.

Buffer stock is key

Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) Senior Fellow Roehlano Briones said the decline of the SSR to 77 percent as of 2022 is not worrisome as long as the country has a buffer stock.

The decrease in the SSR last year, Briones said, may have been due to the damage to local rice supply following typhoons as well the higher rice prices globally. Given this, it is possible that the country’s SSR will increase in 2023.

“[I am] not worried as long as we have sufficient buffer stocks. SSR not an important indicator,” Briones told the BusinessMirror on Monday.

Meanwhile, University of the Philippines Los Baños economist Luisito C. Abueg said in a phone interview that with the 77 percent SSR and the recent imposition of the price cap, the SSR could further decline this year.

This may be possible if, given the price caps, farmers were discouraged from planting, thereby reducing the level of rice production. This is natural for farmers, he said, given that they also need to earn.

Another scenario that could lead to a lower SSR this year may be the decision of some traders to hold on to their stocks of good rice varieties to escape the price cap. This may also lead to a lower SSR, which is the level of supply versus the country’s demand, this year.

Abueg also said El Niño, which is expected to be longer than usual, could also lead to a lower SSR this year. “[There are estimates] that the El Niño will affect one planting season and that would possibly contribute to the [lowering of the SSR].”

While any shortfall can be plugged by importation, Abueg said that based on recent experience, the importation of rice has not led to any decrease in prices. The theory is, if there are more imports, there is more supply, and this would reduce prices but this did not happen as rice prices remained expensive.

Road to 100 percent?

In a recent Senate hearing, Sebastian revealed that the country would need to produce at least 24 MMT of palay to hit the 100-percent SSR.

The volume would translate to some 15.696 MMT of rice, based on a 65.4-percent milling recovery rate used by the PSA and the Department of Agriculture (DA).

In April, the DA said it aims to achieve 100 percent self-sufficiency by 2027 through its Masagana Rice Program (MRP) 2023-2028, which seeks to group local farmers into rice clusters to achieve economies of scale.

Under the MRP, the agriculture department targets to improve local palay production to as much as 26.86 MMT.

“To achieve the stated goals, the DA shall implement four key strategies: climate change adaptation, farm clustering and consolidation to promote convergence of interventions; value chain approach; and digital transformation of the Philippine rice industry,” the DA said.

However, in June, President Marcos Jr., concurrent agriculture chief, revised the department’s rice SSR target to just 97 percent under his watch.

“You do not have to really go to 100 percent because the 3 percent are those niche products like organic or special grain like Japanese rice,” Marcos said, speaking partly in Filipino.

“But with the 97 percent [rice sufficiency], we can say we can feed our citizens sufficient rice,” he added.