It was bound to happen: 6,000 idle housing units have been occupied by the poor and homeless since March 8 in a demonstration called “#Occupy Bulacan.”

Never has the government and its shelter agencies faced such a confrontation with its poorest citizens. An unprecedented undertaking by thousands of urban poor families has set the course for unearthing the depth of the country’s housing problem. An estimated 18,000 individuals have taken over communities, and the backlash from the authorities has been malicious, to say the least.

Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap (KADAMAY), the national alliance for the urban poor, is leading #OccupyBulacan, an organized demonstration to redistribute idle housing to Filipinos without a home. The group estimates that in Bulacan alone there are around 8,000 more vacant houses, most of which have been vacant for five years or more.

The units are spread across six housing projects in Bulacan, a province north of Metro Manila — two were meant for uniformed personnel, like police and military, while the other four were established for the relocation and resettlement of informal settlers.

According to a report released by the National Housing Authority in September 2016, much of the housing for the national police and other uniformed personnel in the country remain unused. Only 8,397 out of 60,738, or 13 percent, of the houses are not vacant. Officers have previously criticized these projects as “squatter treatment” and thus opted to forego living there.

While the NHA has yet to reveal the number of empty houses in other relocation projects for informal settlers, given the magnitude of these resettlement areas throughout the country, it’s safe to say that there are a lot more.

What has probably shocked government officials the most is that they failed to anticipate #OccupyBulacan: a bunch of vendors, drivers, scavengers and the like pulled one over them. That must hurt. It especially hurts people who have lorded over, manipulated and hurt urban poor Filipinos at every turn. They must have felt powerless, at least for a few days, which probably scared them.

Crisis unraveled

All these housing units were built under the longstanding government social housing program, Socialized Housing. It’s a scam, there is nothing “socialized” about it. Housing projects are erected by private corporations and developers hired by the NHA. These companies receive tax breaks among other financial incentives and are fully paid once the all houses are standing.

Moreover, the entire cost of land development and construction is shouldered by the beneficiaries plus a markup. The average costs incurred for each unit in Bulacan is about US$4,800, and yet the beneficiaries

of these units are made to pay up to US$8,000 over a period of 30 years. That may not be much for financially stable families but for people struggling for regular work and pay, it’s a burden they can do without.

In 2015, a group of scientists concluded that the structural integrity of the units under the socialized housing program was substandard and did not follow the guidelines of the National Building Code. This meant substandard construction vulnerable to floods and deterioration. Locals would often lament that for less than US$4000 they could build a better house.

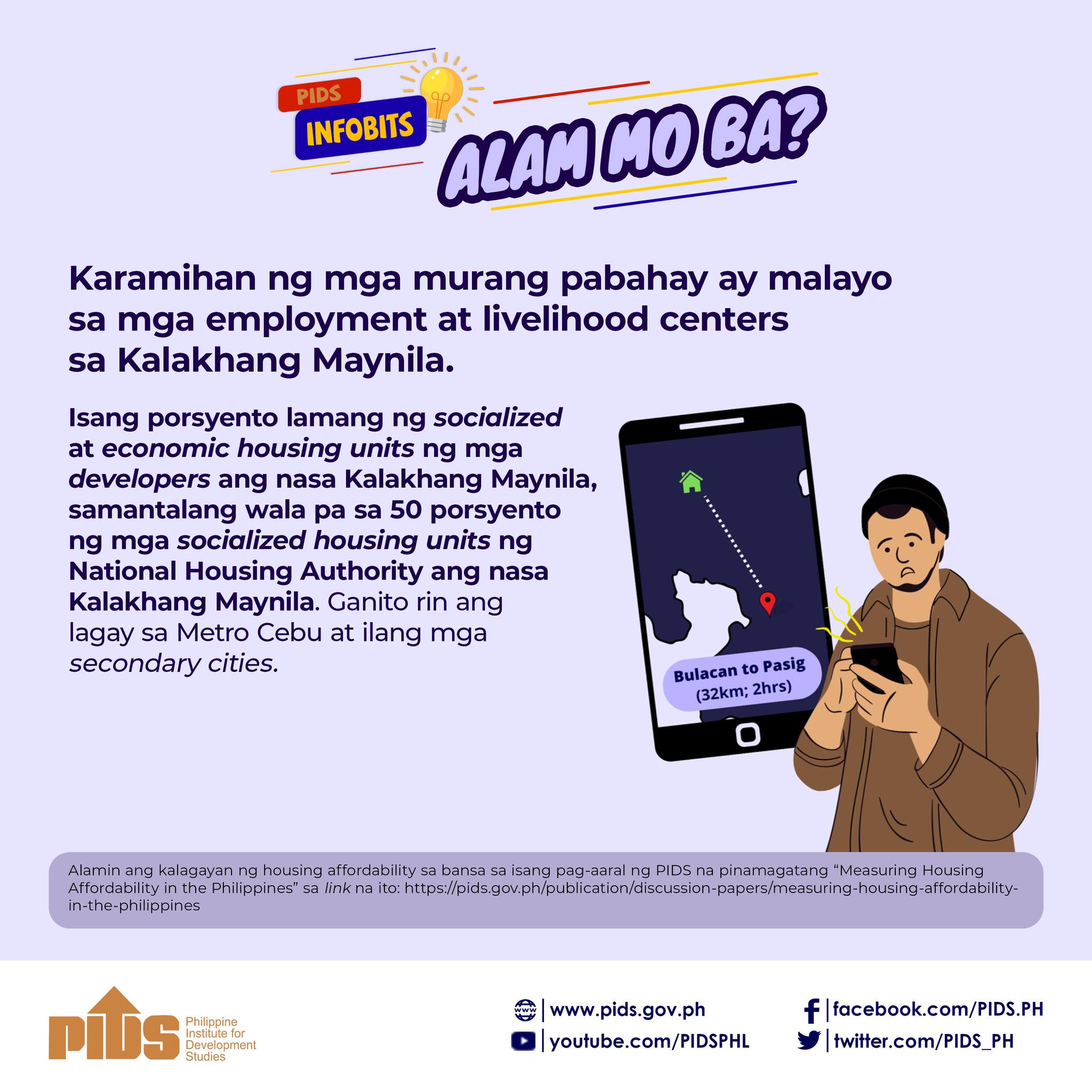

According to a study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies in 2012, the collection rates for off-city sites, like Bulacan, raked in a measly 4 percent. The Commission on Audit said that in 2013, socialized housing in Bulacan posted the highest number in amortization arrears and debts.

Add to this the fact that water and electricity are scarce in the projects; some haven’t had water or electricity for two years. The Vice President previously estimated that 50 percent of these sites do not have potable water, and in some cases, it can be poisonous; three-year-old Justine Billiones died last year after drinking the tap water in one of Bulacan’s relocation site.

The highest minimum wage in the region is US$7 per day. If you’re lucky enough to receive that and take into account food, education and health fees among other essentials, it’s no wonder amortization will still prove too much. But why are the poor paying for supposed publicly funded housing anyway? The NHA can guarantee the profits of corporations but not shelter for the poor? I don’t see how they can still be categorized as “beneficiaries.”

Absurd costs, a lack of utilities and facilities, and their long distance from any decent job opportunities are the reasons behind the immense surplus of idle housing units. It is precisely the failure of the current shelter policies on a systematic level that led to #OccupyBulacan. As KADAMAY points out, “We made use of the idle homes. We did the government’s job for them.”

If not for the occupation, most of the public wouldn’t even know about the state of public housing in the country. As the NHA faced a barrage of questions on the matter, it also became apparent that they did not even have a proper inventory of the residents in these projects.

Standpoint

#OccupyBulacan has taken the country by surprise. A flurry of angry and hateful reactions poured in on the day it started, and news coverage was constant, though often spiteful.

A distinctly offended middle class reacted with utmost disgust. The occupiers were labeled as lazy, ungrateful, law breaking “invaders” who stole houses and disrupted peace — all familiar slurs whenever the poor do anything to challenge the status quo.

Though anticipated, these violent objections still baffle me. Would we rather have Filipinos on the streets than in homes of their own? Wasn’t the “People Power Revolution” that overthrew the Marcos dictatorship an illegal action that was supported by many of the middle class? It was collective will that spoke and so is #OccupyBulacan which is guided by an assertion of the inalienable right to adequate shelter.

There is definitely something wrong with blaming poverty on the poor or condemning them for aspiring to a better life. Sympathy is needed, but what the homeless need more is solidarity.

On the other hand, those in power opted for a more forceful approach. President Rodrigo Duterte addressed the matter by saying, “Frankly speaking, you sometimes say, ‘Obey the law, no Martial Law.’ But you want to ignore the law. You cannot do that. I will force the issue with eviction. It’s anarchy and also made government appear inutile.”

Since the first day, police and military swarmed the projects, even putting up camps in resettlement areas outside Bulacan in fear of anyone replicating the action. Food blockades were enforced when supporters would bring donations, and cash was offered so that occupants would leave.

In response, barricades were raised at the entrances of the communities, and protests were initiated by a wide array of groups at both the NHA and the Presidential palace. Students, health professionals, artists, migrant groups, unions, lawyers and the clergy held various activities in support of #OccupyBulacan.

Entering each of the six sites took enormous planning, synchronization, timing, greater political consciousness and courage. Additionally, the homeless of Bulacan had been holding talks with the NHA, and even the Presidential Palace, almost every month since August 2016. They would hear the same promises yet never see efforts to address their concerns.

This isn’t just about housing but a political statement on a persistent injustice doled out by the government and its shelter agencies.

Last minute victory

Duterte’s orders prompted memories of horrific scenes that were caused by eviction orders under the past Noynoy Aquino administration; 1.4 million Filipinos were displaced and 23 individuals killed in the process. For a regime as bloody as Duterte’s, the deadline day for eviction, March 28, looked like it would get messy.

“Years to get a house you cannot afford but the administration can kick us out in just seven days,” said one of the residents after an eviction notice was formally served on March 20.

However, a dialogue between KADAMAY and the NHA took place a day before the eviction. The eviction was canceled and the NHA are now looking into ways to accommodate the new neighbors or relocation residents.

Pursuing an eviction without the government accounting for why public funds were spent on a massively unutilized project would further tip the scales against them. The agency buckled and is now forced to take a long hard look at its deficiencies.

The president followed suit. On April 3, Duterte announced that the housing units would be awarded to the occupants, and uniformed personnel will be provided with a newer set of housing units. In his speech, he said, “Let’s not trouble the people there because they’re fighting back.” The concession is a testament to the collective strength of a people usually maligned by most in society for their social status.

But this was the first of many negotiations. One critical issue that hangs in the air is if and when the houses are awarded, will the same payment schemes be implemented? KADAMAY has responded with a resounding “no,” as the same problems and failures that led to thousands of idle homes will merely be repeated.

This is not the end of the story. The policies that disenfranchise millions of urban poor Filipinos and caused this mess are still in place. A deadline for profiling and affixing validations for the occupants has been set for May 30. A lot can go wrong with the validation process. The NHA doesn’t look too happy that their shortcomings and inclination to corporations have been exposed further.

Will this set a precedent? Definitely. From defending communities from demolitions to entire takeovers present a new range of possibilities for social movements of both rural and urban poor Filipinos. These are interesting times and many poor Filipinos may very well occupy 2017.

Editor: Olivia yang