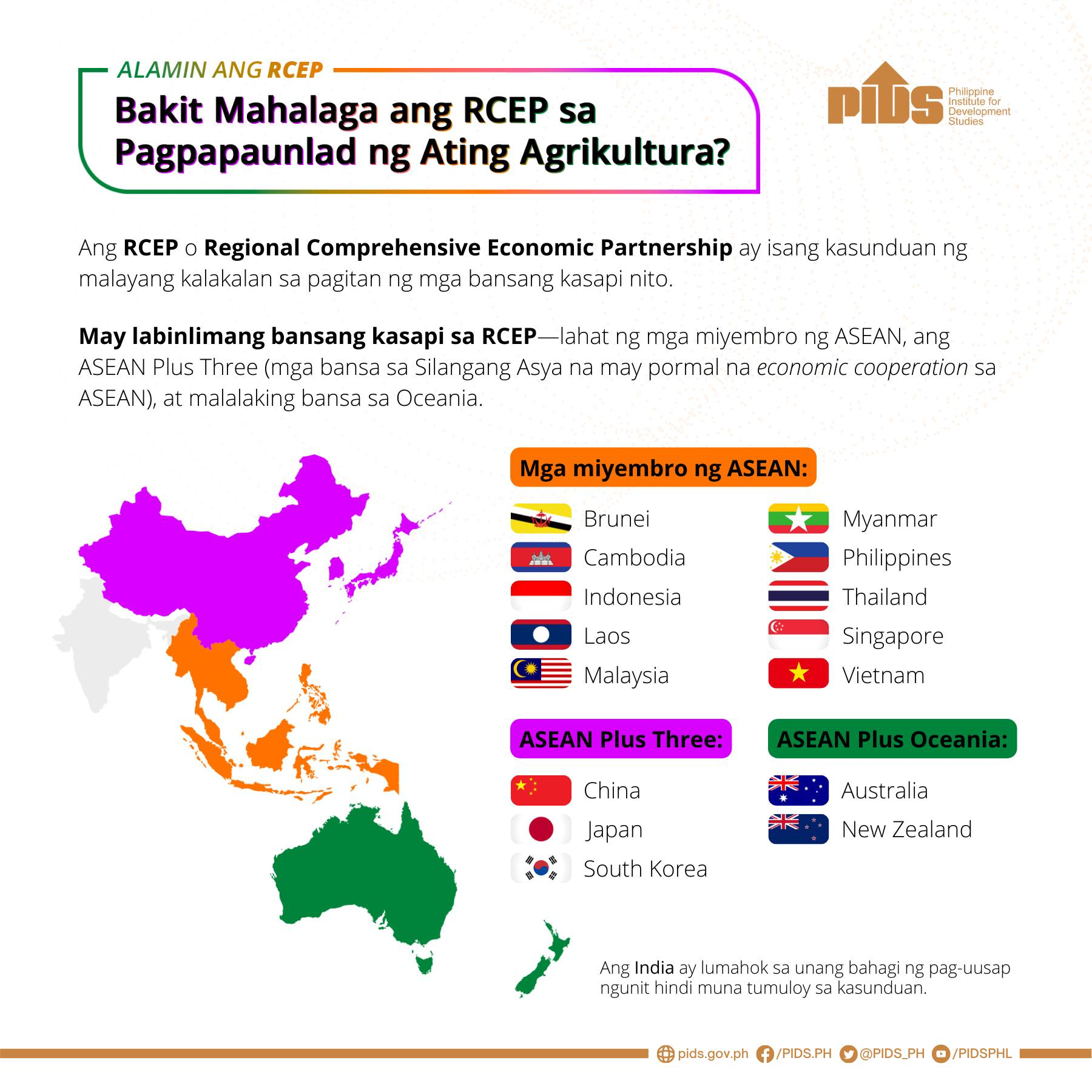

Asia-Pacific is keen on making progress on regional cooperation, with economic integration within the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations as a key milestone set for 2015.

Despite regional economies growing at breakneck pace, inequality gaps are hampering efforts to turn ASEAN into a single economic community – an ambitious move considering the enormous distance between ultra-modern Singapore and dirt-poor Myanmar, still emerging from the shadow of decades of military rule.

Read: Why a fully integrated ASEAN is not (yet) possible

But developing nations in Asia are telling donors they don’t want handouts in the form of official development assistance grants and loans, but rather investments from the private sector to develop their economies in a sustainable way to reduce future dependence on foreign aid.

So what role can the international development community play in the continent’s future regional integration efforts, and in helping bridge the inequality gap?

Devex asked three experts during the launch of the Asian Development Bank’s "Asian Economic Integration Monitor,” a bi-annual review of Asia’s regional economic cooperation and integration covering the 48 regional members of the Manila-based institution.

"We need more investment rather than donations,” said Diwa Guinigundo, deputy governor of the Central Bank of the Philippines. "[Donors] can play an important role … but [they should] be conscious of the so-called spillover effects of their policies. Let’s treat each other as partners.”

While acknowledging that donor funds are crucial to finance investments in emerging markets like most of ASEAN’s member states, Guinigundo stressed that partnerships are "more important than being recipients of donor grants … in the context of pursuing inclusive development.”

‘Don’t marry for money’

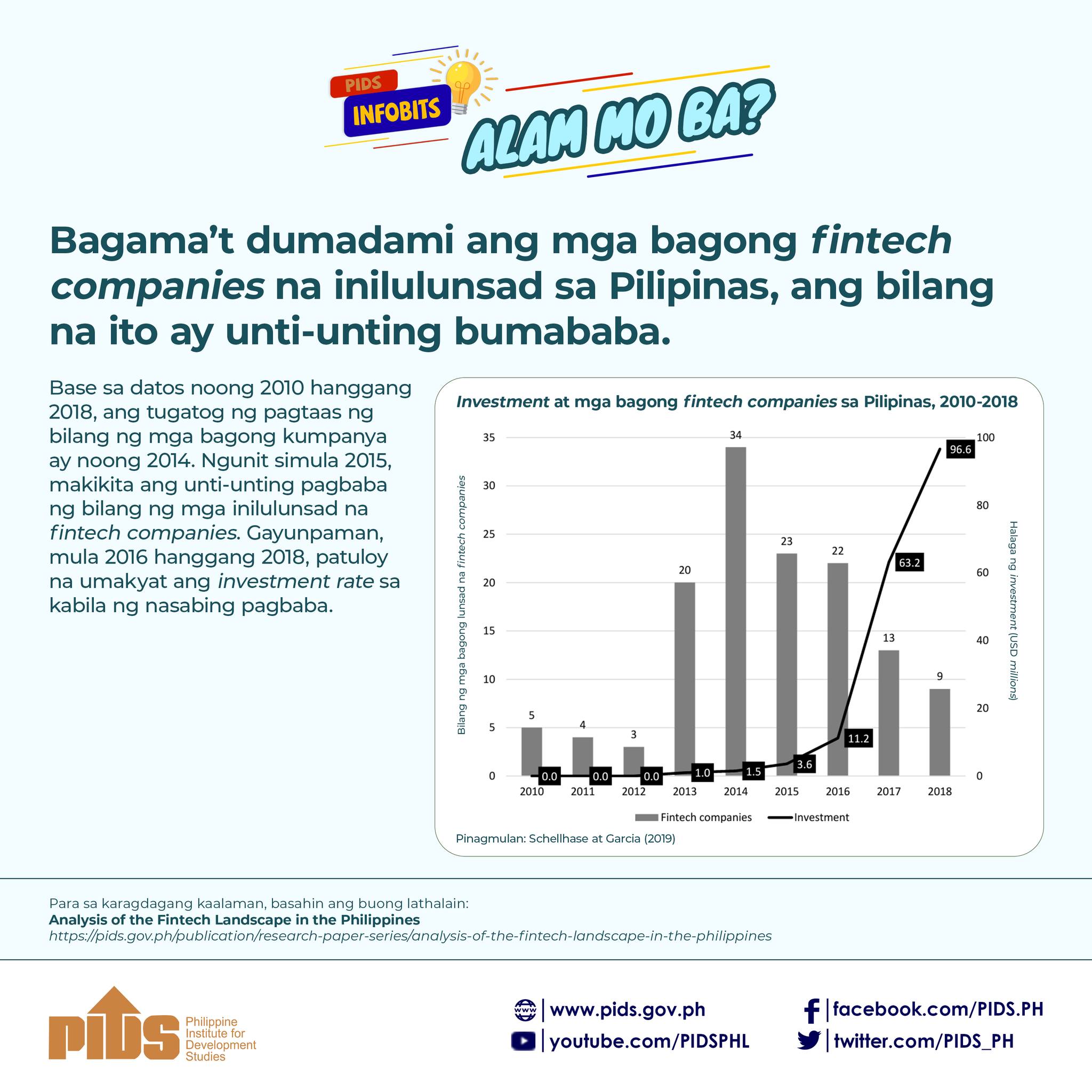

Gilbert Llanto, president of the Philippine Institute of Development Studies, explained how in the changing landscape of development finance, his country has evolved from being heavily dependent on ODA to relying much more on private capital – especially remittances – through successful reforms of the fiscal system.

That doesn’t mean, though, that international financial institutions have become obsolete for developing nations like the Philippines.

"I think the World Bank and especially ADB still have an important role, because they will be tapped to finance [projects for the] public good, like disaster risk management,” Llanto said. "Donors bring in technical expertise and capacity, and this is a win-win role, not a diminished [but rather] very strategic role.”

Money is not the object, according to Federico Macaranas, a senior professor at the Asian Institute of Management, a prestigious Manila-based think tank.

"If you marry for money, then it’s not a partnership. So why are poor countries always looked at as recipients of money? Because the banking community thinks it’s money that drives the world,” he explained. "The world is awash with money, yet money has not solved the problems of the world [because donors] don’t engage the very people who have solutions to the problems of poverty.”

Macaranas gave the example of the SARS epidemic that swept Asia in 2002-2003, which was not fixed by expensive Western pharmaceutical drugs but by local expertise that drew on indigenous remedies to contain the disease.

"Why do we shun all this indigenous knowledge? The international development community knows it can learn from this,” he said. "It’s not the educated engineers who know our conditions best, but the indigenous farmers who know many things in their local communities that matter more for the development community.”

It’s better to know more about what locals can offer, he said, "rather than say ‘here is money’ to construct a house [after Typhoon Haiyan] when all [the affected communities] wanted was boats to give them a livelihood” that would give them independence to rebuild first their lives and then their homes.

"Development partners must know intimately what the locals want,” he concluded.

ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL INTEGRATION Foreign aid in Asia’s regional integration: Less donations, more investment