LAST week, we were able to delve into the barriers and bottlenecks that constrain young pupils from being educated. We have discussed on the socio-cultural demand-side barriers, namely perceptions on the child’s readiness and the parents’ educational levels.

For Part II of this two-part series. We uncover the demand-side barriers that are related to economic status of the consumers of the merit good (a good that provides positive effects to the consumer), which is education, as well as the supply-side bottlenecks.

The first economic demand-side barrier is poverty. The Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) reported a poverty incidence of 21.6 percent in 2015. This means that about one-fifths of the Philippine population are living below the poverty threshold, where the sectors with the highest poverty incidence are the fishermen, farmers and children who belong to poor families.

Public education is essentially free here in the Philippines, but the PIDS paper noted that dire poverty has direct effects on schooling like when the family cannot afford to buy school supplies or do not have enough money for fare going to and coming from school. The indirect effects that puts pressure on the resources and time of parents are those that are more alarming.

There are cases where pupils perform poorly, are chronically tardy or absent, and drop out of school entirely because they are directly (when they are asked by their parents to help out) or indirectly (when children volunteer to help out) forced to help earn for their family’s livelihood.

A child comes to school late because he had to earn for their family’s food, either by staying up late or waking up very early. When he is in school, he feels tired or sleepy, and cannot concentrate on the lessons, resulting to poor performance. When all these burdens pile up, he is forced to drop out.

However, the PIDS study emphasizes that the decision to drop out of school precedes the decision for the child to work. They were forced to work since they do not go to school anyway. It is not that the parents do not value education, but since they are poor, they have no choice but to stop sending their child to school because they can’t afford it.

Otherwise, they would have to forego some meals. That is the choice they have to make, will they send their kids to school or will they eat that day?

Another economic demand-side barrier is the household’s perceived benefits of education. Basically, parents look at the expected returns of their investments on the education of their children. The ‘myth of parental indifference’ is a term used by some researchers to define the event where a child drops out of school and the blame goes to poor and uneducated parents who allegedly do not value education.

When the parents are poor, they cannot send all their children to school all at the same time. They have to make a decision who among their children should be educated first. It is usually not the eldest, as he/she needs to help the parents tend the younger siblings or help earn livelihood. It is the one who performs very well and has the highest likelihood to complete school. This is the one who has the highest potential for returns on their investment on education.

The PIDS paper mentions that there are lower achievement expectations on boys compared to girls. Furthermore, girls are believed to be more likely to finish school, regardless of what job they ended up having and how much they will be able to contribute to the family’s livelihood, they are considered to be the better investment.

There are other economic demand-side barriers including income shocks (when income drastically falls due to unexpected events like job loss, unplanned pregnancies, deaths, marital separation, etc.), migration (moving from one place to another, and children are pulled out from school at the middle of the year), disasters or conflicts (these may affect adversely household income), and poor health of children (makes the pupils more vulnerable to illnesses, eventually dropping out).

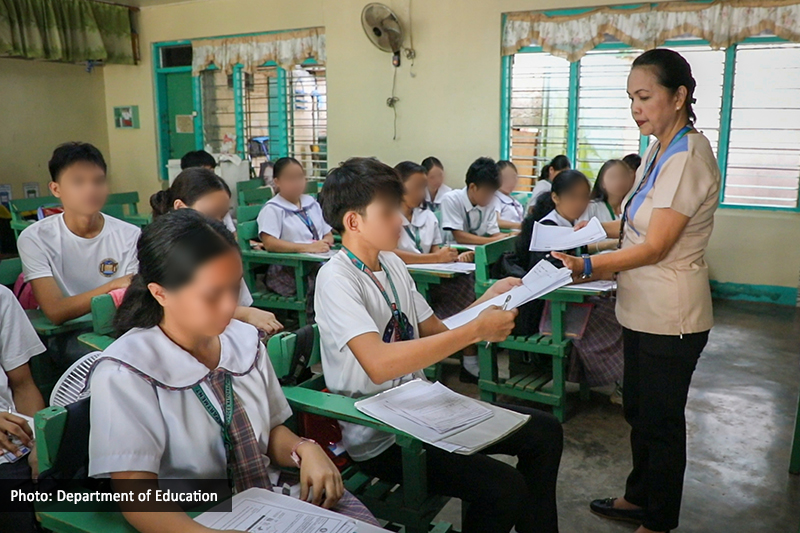

There are also supply-side bottlenecks. The Department of Education has always been one of the primary agencies with a sizeable budget. However, year after year, there is always that problem on the lack of teachers, classrooms, facilities and school buildings. There are still a few number of barangays that still do not have an elementary school, and children have to walk some distance to attend the nearby barangay’s elementary school.

I personally witnessed several schools in Tuba and Itogon in Benguet where two grade levels are taught in one classroom by one teacher. The multi-grade level classroom is a result of not only the lack of teachers, but also the lack of classrooms. There is a shortage of classrooms that some classes are just conducted under mango trees. I used to think that this is a hyperbole, but in one of my field assignments, I saw it for myself so it really happens.

Learning materials, like textbooks, reference books and teaching aids are also incomplete. Teachers even spend for their teaching aids despite their low salaries. Unless and until the problems on the number of classrooms and school buildings, the number of teachers and completeness of learning materials, the quality of education would always be questionable.

Studies show that children, particularly the boys, lose their interest in going to school primarily because of the quality of education offered in public schools. Without the motivation to attend school and the proper guidance of the parents, these children would eventually drop out of school.

Notwithstanding the fact that education is a basic necessity, a merit good and a good that produces positive externalities (effects to third parties not included in the economic transaction), there are still children who drop out of school. The reality of poverty confronts these children. Their parents may not have been very responsible and were not plan their family, procreating more than they can feed and send to school. They were not prepare for a stable livelihood to support a family. They were not able to foresee a future where they do not need to make a choice between education or food/shelter.

Their children are victims of their bad choices. It is not fair for the children not to be given the opportunity to study and finish school, and get him/herself out of the poverty he/she was born into. However, this is not the end of the line for these children. There is still hope. Poverty should not hinder you from obtaining education, especially now that even tertiary education is now essentially free.

There are very many success stories that I know of. One story is that of someone who comes from a poor family, with uneducated parents and with many siblings, who overcame many challenges along the way while studying, who finished two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree, and studying toward achieving another higher degree, and who now works and is a responsible citizen who contributes positively to society, in general. That is the author’s story of survival to success. It could be yours, too.