How serious is the housing shortage in the country?

As of June this year, the housing backlog was pegged at 6.658 million units.

Of this number, 3.753 million are intended for informal settler families.

The rest, presumably, are for those who rent their dwellings on a monthly basis but would like to have homes they can call their own.

In July, President Marcos issued Executive Order 34 declaring the mass housing project of the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development as a flagship program of his administration.

The ambitious goal of the program is to provide as many as 30 million Filipinos across the country with a roof over their heads by the time the Marcos administration leaves office in 2028.

This means the construction of at least one million low-cost or affordable housing units a year for a combined 6.15 million units in the next five years.

But would this be a purely government initiative?

Apparently not, as it would rely as well on the private sector to deliver the needed housing units.

The DHSUD and the National Economic and Development Authority recently agreed to raise the “outdated” price ceilings for the government’s urgently needed socialized housing and condominium projects.

By increasing the price cap to more accurately reflect escalating construction and development costs since 2018, the government agencies hope to entice the private sector to participate more actively in the “Pambansang Pabahay para sa Pilipino” or 4PH program.

According to Housing Secretary Jose Rizalino Acuzar and NEDA Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, they were well aware that current price limits for socialized housing “no longer respond adequately to prevailing market conditions, including rising development and construction costs, thereby discouraging the private sector from building affordable houses for low-income and underprivileged families.”

Hence, considering such factors as affordability for buyers and the impact on the property development sector, socialized housing projects will now cost a maximum of P850,000 from the current P580,000 for units with a minimum floor area of 28 square meters to as much as P1.145 million for bigger units.

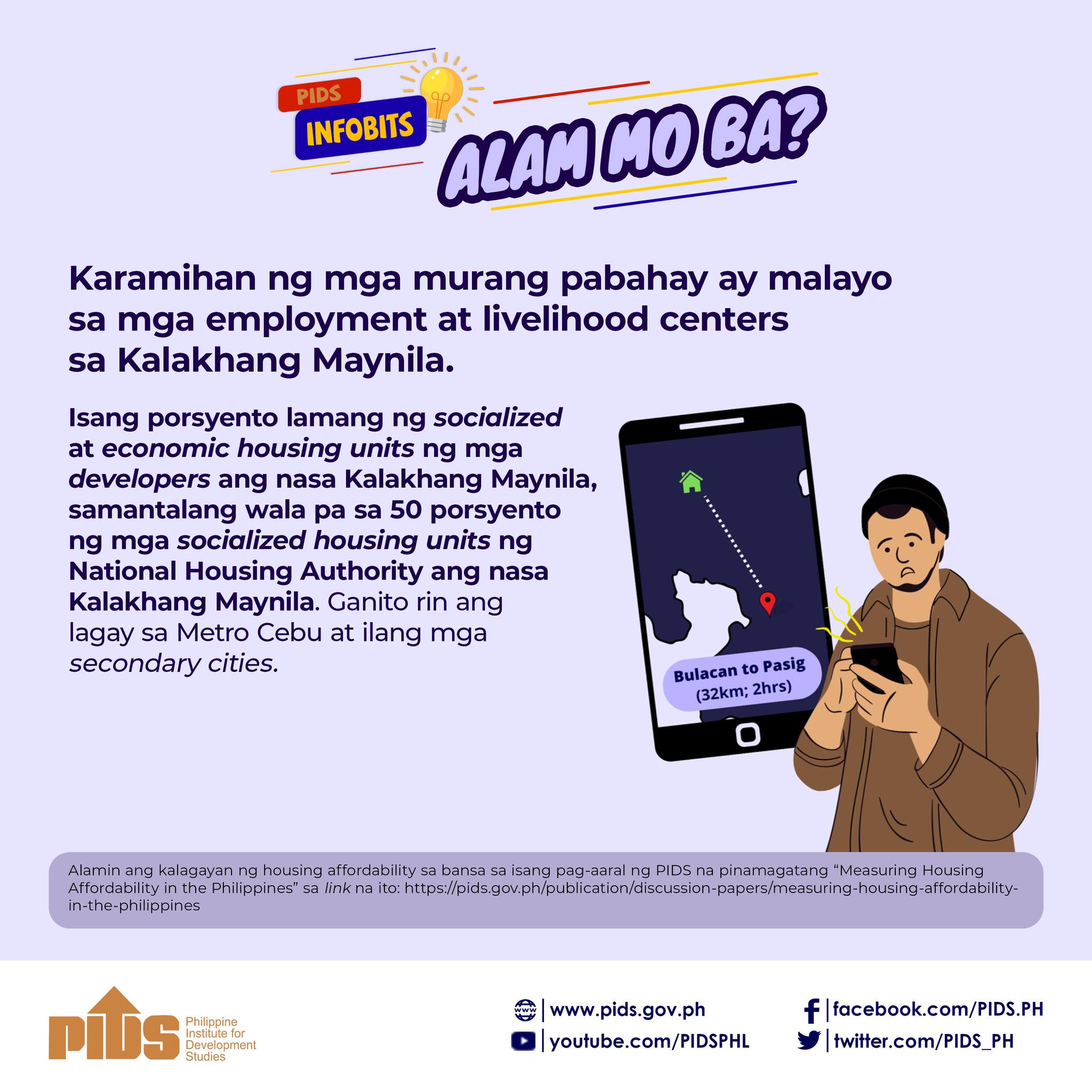

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) has noted that private sector investments in the mass housing sector have steadily declined, since developers could no longer recover their costs or make a decent profit at previous price caps.

Even with the adjusted price ceilings, however, private developers are unlikely to rush in big numbers to help the government to reduce the gargantuan housing backlog. Why? Raising the price ceiling means that the cost of the finished housing projects will now go even further beyond the reach of the target market: the minimum wage earners with incomes of less than P25,000 per month.

In other words, the suggested price ceilings, while designed to attract private developers to go into construction of low-cost housing for the masses, will also jack up the prices of finished units to levels that will not be affordable by minimum wage workers who have no means to pay the monthly amortizations.

All things considered, we think the proposed solution to the housing backlog is not really a solution, but a clear signal to policy makers to go back to the drawing boards and think of a better way to raise capital for low-cost mass housing.

BARMM gears up for self-rule

The good news is that the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao is up and running, fueled by a proposed P98-billion operational budget for next year.

Education gets the biggest chunk of its budget in keeping with the regional government’s promise to make quality education accessible to all.

According to BARMM Interim Chief Minister Ahod Ebrahim, the proposed budget for 2024 submitted for approval by the Bangsamoro Transition Authority, the BARMM’s interim governing body or parliament, showed their commitment to address the region’s needs, propel economic growth, and improve the overall quality of life for the Bangsamoro.

Aside from education, which gets P30.2 billion of the proposed budget, the two other biggest allocations will go to infrastructure, with P17.6 billion, and health, with P6.6 billion.

The 80-member BTA, which was formed in 2019 as a vital part of the peace accord reached between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front-led rebels, will commence deliberations of the proposed budget beginning this month.

The BTA, whose term has been extended from 2022 to 2025, is mandated to pass crucial legislation to operationalize the Bangsamoro Organic Law that created the BARMM and exercise legislative and executive powers during the region’s transition period.

Of the P30.2 billion earmarked for education, P754 million will be used for the construction of schools, classrooms, and libraries, in recognition of the vital role of education in fostering inclusive growth, innovation and sustainable development.

On the other hand, most of the P17.6 billion allotted to infrastructure would be used to build facilities meant to strengthen the regional economy and reduce poverty in the region.

We’re glad that BARMM is on course and ready, willing and able to consolidate the peace won through painstaking political negotiations that ended decades of bloody fighting.