MANILA, Philippines—As the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement officially entered into force for the Philippines, a month after the Senate ratified the trade deal, debates on its impact—the good and the bad—persist.

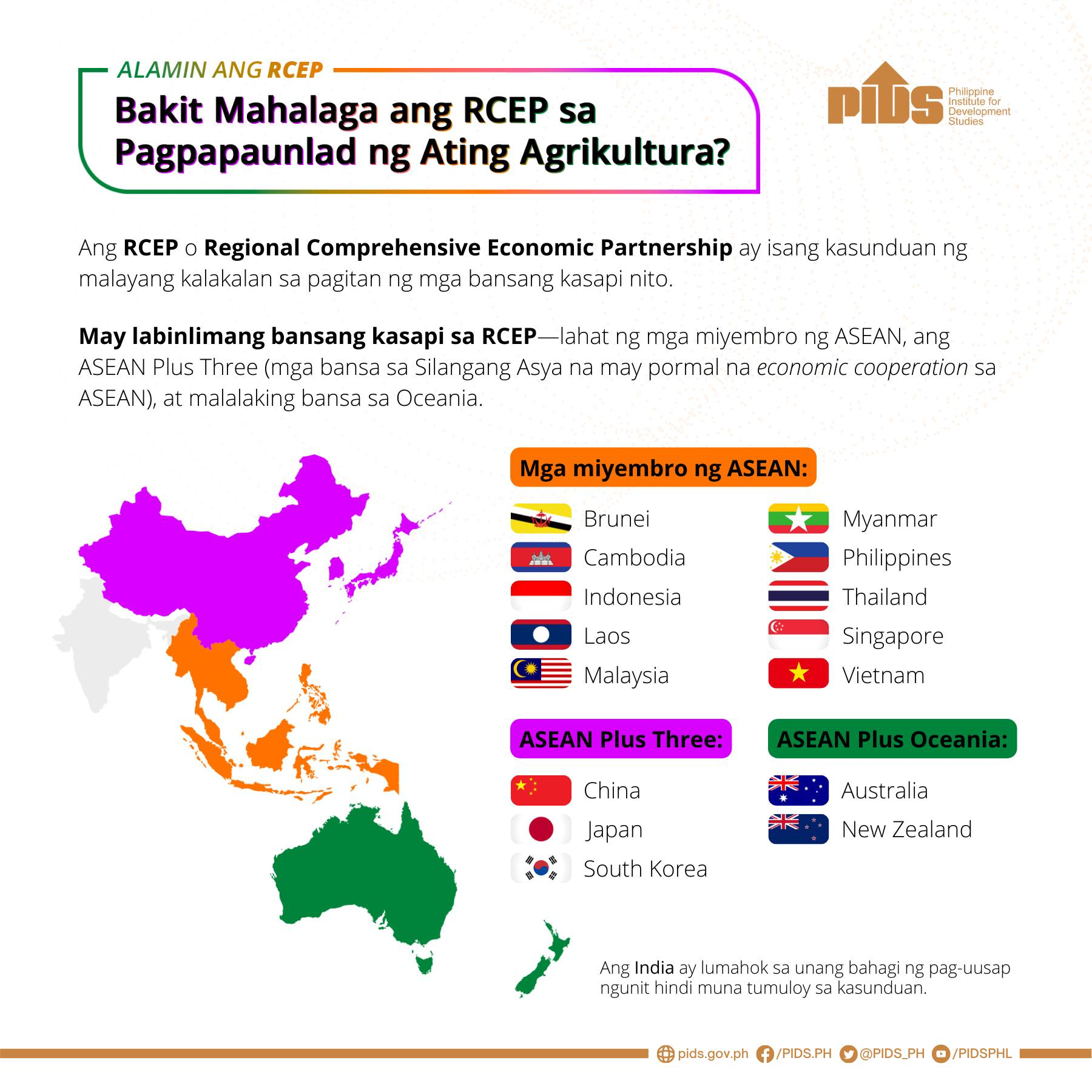

RCEP is a free trade pact among the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam—and its five FTA partners: Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand.

After eight years of negotiations among RCEP member countries following its conceptualization in 2012, the agreement was signed in 2020 and entered into force in January 2022 after the required number of member states that should ratify or approve the landmark deal was met.

Dubbed the world’s largest free trade agreement (FTA) to date, it provides preferential arrangements, including market access, in all participating countries. The agreement covers trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement and other issues.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The goal of the RCEP is to remove tariffs on at least 90 percent of commodities traded among member countries, while also strengthening regulations for non-tariff measures.

In September 2021, then-President Rodrigo Duterte signed RCEP. Over a year later, in February 2023, the Philippine Senate made the country’s participation in RCEP official after it ratified the trade deal—making the country the last signatory, aside from Myanmar, in the FTA, or free trade agreement.

Last April, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balicasan, who heads the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), announced that President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has issued Executive Order (EO) No. 25 operationalizing the country’s tariff commitments under the RCEP.

Two months after, RCEP entered into force for the Philippines, which the government said would lower the prices of commodities for consumers and attract more foreign investments into the country.

Both previous and current administrations have touted the practical benefits of RCEP. But several agricultural and farmer groups have repeatedly expressed concerns and strong opposition to the regional trade deal—even after its ratification earlier this year.

Global impact of RCEP

A report published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) noted that the benefits of RCEP to its member states were expected to be significant.

RCEP members account for around 30 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP). Trade in goods among countries participating in RCEP was close to $2.5 trillion in 2019, or around 13 percent of global trade.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“RCEP should be instrumental to advance trade relationships between the economies whose bilateral trade relationships were not previously regulated by any trade agreement,” said UNCTAD.

“The RCEP agreement aims to further advance regional trade by providing members with better market access conditions largely by reducing tariffs and implementing trade facilitation measures, therefore bringing RCEP countries a step closer to becoming a regional trading bloc,” it added.

A study published by Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) last year listed the benefits promised by RCEP to member countries.

According to the study authored by John Paolo Rivera, economist and associate director of Asian Institute of Management, and Tereso Tullao Jr., economist and assistant professor emeritus at De La Salle University School of Economics, RCEP’s benefits included:

- Add $186 billion to the world economy

- Add 0.2 percent to members’ GDP

- Compensate for 67 percent of income losses from trade war between China and US

- Generate economic benefits bigger than that from another free trade agreement, Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

Amid the promised benefits, however, one question lingers: “What can the Philippines gain from this trade agreement?”

What PH can gain

RCEP covers 50.4 percent of the Philippines’ export market, 67.3 percent of the country’s import sources and 58 percent of foreign direct investments, or those that are meant to build new factories, new offices, and new businesses.

According to EO No. 25, the trade agreement aims to:

- establish a modern, comprehensive, high-quality, and mutually beneficial economic partnership framework

- progressively liberalize and facilitate trade in goods and services through elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers, as well as restrictions and discriminatory measures

- create liberal, facilitative, and competitive investment environment.

A paper by the Bureau of Trade and Industrial Policy Research (BTIPR) uploaded on DTI’s website said that from 2016 to 2020, RCEP participating countries (RPC) were among the top export markets of the Philippines.

In the same period, the country’s exports to RPCs averaged 49.9 percent of total exports to the world. In 2020, exports to RPCs amounted to $33.4 billion, or 51.2 percent of the Philippines’ total exports to the world.

In addition, RPCs were also the country’s top import sources, averaging 66.8 percent of total imports during the period 2016-2020. In 2020, the import share of RCEP reached its highest at 68.4 percent with imports recording $61.4 billion

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The BTIPR study said an average of 60 percent of Philippine total trade during the five-year period was with RPCs. While Philippine trade was largely with the US and Europe, it was “increasingly going towards RPCs at an average growth of 3.7 percent for the last five years,” the report said.

With the commitments made by RPCs, including the Philippines, under the RCEP, Rivera and Tullao explained that the country’s participation in the trade deal would open more opportunities for Filipinos to generate income through supplying business and professional services in RCEP member nations.

It would also help the Philippines invite more enterprises, investors, and professionals to engage in business in the country.

“This can eventually develop human capital, infrastructure, tourism, and other industries, and enhance domestic productivity in the long run. While liberalizing the economy will pose competition with domestic enterprises and infant industries, protection can still be accorded,” the economists said.

“Liberalization can be considered for industries where the Philippines has inadequacy, such as utilities, telecommunications, construction, and infrastructure. These areas have been the country’s key constraints that impede economic takeoff,” they added.

In a statement, Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno said RCEP will expand the Philippines’ market access to goods and services. Additionally, the trade pact will also further attract more and create “more and better jobs” for Filipinos.

“The agreement will also support MSME development and drive participation in the global value chain,” said Diokno.

“Philippine manufacturers would also benefit from wider sources of raw materials due to zero or lower import duties on their inputs as well as more flexibility in the rules of the FTA on product manufacturing,” he said.

“Skilled Filipino professionals and business persons in legal, construction, engineering, and banking services will be given preferential treatment to practice their professions in participating nations,” he added.

However, Rivera and Tullao stressed the opportunities stemming from the country’s participation in RCEP can only be maximized by improving the country’s strengths in competitiveness, language proficiency, cultural adaptability, human capital, and government participation.

‘Winners and losers’

While policymakers and supporters of the agreement detail the benefits of RCEP, some have noted that it is also equally important to look at its possible downsides and acknowledge that there are “winners and losers” as a result of the regional free trade.

“The problem with free trade agreements in the local context is that their advocates tend to highlight only the benefits they would bring, while simultaneously downplaying their ill effects,” an editorial piece published by INQUIRER.net last April noted.

“Their proponents have always tried to win over the public by promising cheaper consumer goods, while conveniently forgetting the economic law that such a benefit will have to be paid for one way or another,” it added.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

It has been mentioned in past statements that the perceived winners in RCEP are the industry and service sectors, while the perceived losers are in the agriculture sector.

According to Raul Montemayor, chair of the Federation of Free Farmers Cooperatives Incorporated (FFFCI), most of the projections of some economists highlighting what the country can gain from RCEP are based on “economic theories and unrealistic assumptions that rarely play out in the Philippine setting.”

“Free trade simply has not worked for our agricultural sector, particularly our small farmers and fisherfolk. How then can we believe all these rosy projections about RCEP, if the people making them have been so wrong previously?”