AS the curtain of “unfair trade” closes for the interests of farmers from developing countries, the Philippines stands in the middle: no one’s going home yet.

When the Philippine delegation to the 11th Ministerial Conference (MC11) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where more than 160 trade officials met to discuss the future of global trade, they came with one goal: protect the country’s small-scale farmers.

The Ministerial Conference, which is attended by trade ministers and other senior officials from the organization’s 164 members, is the highest decision-making body of the WTO. Under the “Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO,” the Ministerial Conference is set to meet at least once every two years.

Discussions during the Ministerial Conference revolve on issues that would pave the way for the growth of global trade. These issues may include talks on agricultural goods, export subsidies, farm productivity, technology, gender and anything under the sun that has something to do with trade.

But some global trade issues have remained contentious, such as negotiations on agriculture, including commitments on tariff cuts and protecting domestic farm sectors.

Safeguard

JUST before the Philippine delegation left for MC11, which started on December 11, President Duterte instructed them to get the best for Filipino farmers.

Of course [we will protect the farmers]. The President will always protect the farmers. But not to the point of straining the Philippines’ relationship with other countries,” Agriculture Secretary Emmanuel F. Piñol said in an interview during the opening of the 14th Regular Session of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission held in Pasay City on December 3.

We have to negotiate what is best for Philippine agriculture. I will just play a supporting role to the trade secretary because he is the head of the delegation,” added Piñol before heading for the airport that day. “But I assure the Filipino people that, as agriculture secretary, I will make sure that our interests are protected.

At the onset of the three-day MC11, the country’s trade negotiators have already rejected the efforts of rich countries to implement deeper tariff cuts on farm products. The Philippine trade negotiators were lukewarm to the idea of allowing developing countries to protect their domestic industries from harmful import surges.

In his speech delivered before fellow farm ministers, Piñol emphasized that the Philippines will not agree to new agricultural deals without passage of a concrete special safeguard mechanism (SSM) for developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs).

The Philippines once more wants to reiterate its firm decision that none of the priority of the WTO members provide sufficient political basis for us to support any concrete substantive outcome in this conference in the absence of a specific solution on SSM,” he said

This minimum requirement is even critical for the Philippines as members continue to evade the needed reforms in domestic support, especially phasing out trade-distorting support, including an interim commitment to limit supports at the product-specific level,” he added.

Push

PIÑOL urged WTO member-countries to act on the Philippine proposal to establishing SSM if they want to get the Southeast Asian country’s nod on any agricultural deal in the ongoing MC11.

Indeed, time is not on our side and members must not second guess our resolve if we are to make MC11 truly a success,” he said. “I therefore call on members with extreme urgency to act now and engage us on our proposal to have a specific and targeted solution on SSG [special safeguards] for some members on the basis of our proposal under ‘JOB AG 121’ and ‘JOB AG 123.’”

SSM is a trade measure that will allow developing countries to raise tariffs temporarily to deal with import surges or price falls, according to the WTO. It has become one of the most contentious trade issues within the WTO, especially between developed and developing countries.

In 2004 WTO member-countries agreed that SSM will be established for use by developing countries, as indicated in the so-called July Framework. In the 2005 Hong Kong Declaration, WTO developing country members will have the right to recourse to SSM based on import quantity and price triggers.

However, 13 years after the SSM was first floated within the WTO, a concrete framework on it has yet to be crafted. One of the most contentious issues concerning SSM is the “trigger level” and the rate of tariffs that will be imposed.

Under the current WTO Agreement on Agriculture, the Philippines has applied SSG to at least 118 farm commodities. SSG serves as contingency restrictions on imports taken temporarily to deal with special circumstances, such as a sudden surge in imports, according to the WTO.

Proposal

LAST month, the Philippines filed a proposal that sought to improve the current SSG measures within the WTO framework. This was after oppositions on the creation of an SSM were raised.

Raul Q. Montemayor, national business manager and program officer of the Federation of Free Farmers of the Philippines, told the BusinessMirror that since a lot of WTO member-countries derail talks on SSM, the country had to recourse to an alternative plan, which is to improve the current SSG system.

“What we presented is actually an alternative, which is to improve the existing SSG, particularly a price-based SSG,” he said. “It is actually an improved version of the current SSG in the hopes that they would agree on this.”

Montemayor, who is part of the Philippine delegation to MC11, explained that the country proposed the changes as the present SSG regime has stiff conditions making it ineffective to protect local farm sectors.

For one, the formula used to compute a country’s trigger price is still based on 1986-1988 prices, which is somehow inappropriate to present global prices, according to Montemayor.

“For example, for our rice imports, our trigger price is around P4 to P4.50 based on the 1986-1988 formula. But when you buy rice today in the international market, it costs around P15 per kilogram,” he said. “So, in that sense we cannot use the SSG.”

Under the Philippine proposal, the present 1986-1988 trigger price basis for SSG will be changed to a rolling three-year average import price.

Meaning, the trigger price, which is the price point wherein a country could invoke SSG, will depend on the prevailing import price in the recent three-year period.

Furthermore, the Philippines proposed to phase out the current complicated formula for additional tariffs when invoking SSG.

Under its proposal, once the SSG is invoked, affected countries could slap an additional tariff duty on the imported goods by as much as 90 percent of the price difference between the trigger price and imported price.

This is different from the current SSG regime wherein countries will apply additional tariffs for imports as a trade remedy.

“For example, your trigger price for poultry imports is P100 and an P80 chicken enters your border, so that will allow you to invoke SSG. So 90 percent of P20 is P18, then that will be your additional tariff,” Montemayor said.

“You will not set a tariff value in comparison to your trigger price. And this proposed SSG change applies per shipment, because there could be shipments that do not go below trigger price,” Montemayor added.

‘High time’

DURING his speech at the plenary session, Trade Secretary Ramon M. Lopez said inequities in agricultural trade continue to exist as few WTO member-countries maintain their large subsidies on farm products.

“It is high time that members made bold contributions today, once and for all, to address these gross imbalances and inequities in agriculture,” Lopez, who heads the Philippine delegation to MC11, said. “I therefore call on members to substantially reduce, toward elimination, trade-distorting subsidies by phasing out AMS [aggregate measurement of support] and limit supports at the product-specific level.”

The Trade Secretary pointed out that it is high time that an effective SSM be created at WTO as farm sectors of developing countries and LDCs have been damaged by highly subsidized exports for more than a decade now.

“Developing countries and LDCs must also be provided with an accessible and effective trade remedy tool, through the establishment of a special safeguard mechanism [SSM] that can protect their small and subsistence farmers from import surges and price depressions and shield them from subsidized exports,” he said. “After more than a decade of negotiations for SSM and ministers’ reaffirmation of our political commitment, developing countries and LDCs cannot get back home empty-handed once more.”

In a ministerial communiqué, the Group of 33 (G-33), which includes the Philippines, said the establishment of an SSM remains as the priority of the group to safeguard their food security, livelihood security and rural development interests.

“We wish also to reiterate that the Nairobi Ministerial Decision on SSM has strengthened the mandate in the July Framework and the Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration and reaffirms that developing members shall have recourse to both a price-based and volume-based SSM,” G-33 said in the document dated December 10.

“Members shall be engaged constructively and focus the discussion on outstanding issues and refrain from making any linkage with other issues, with a view to find a pro-development and balanced SSM, which is accessible and effective in addressing the impact of import surges and price depressions caused by short-term and cyclical volatilities,” the group added.

Opposition

FOR his part, Montemayor said the establishment of an SSM is a must in the current global trade regime as small-scale farmers remain at risk from highly subsidized imported goods.

“This is our trade remedy and we need this at a time wherein all our tariffs are low. So there’s more tendency for imports to come in and that’s why we need remedies like SSM,” he said.

However, talks on the establishment of SSM in Geneva, Switzerland, before going to Argentina have been stalled as WTO member-countries expressed divergent views on the trade remedy, with most nations showing disinterest to discuss the issue, according to a Geneva-based trade official.

Jonathan Hepburn, agriculture senior program manager at Geneva-based International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, said the passage of an effective and concrete SSM at the WTO has been delayed due to changes in priorities and interests of member-countries throughout the years.

“The negotiating dynamic at the WTO has evolved significantly since the Doha Round talks were launched in 2001—partly because government policies and international markets have changed, and partly because talks on trade have moved ahead in other fora, such as through bilateral and regional talks,” Hepburn told the BusinessMirror.

“Today, a number of exporting countries say they are only willing to pursue talks on a special safeguard mechanism as part of a broader negotiation on market access—including both developed and developing country exporters,” he added.

Hepburn noted that the Philippines’ negotiating stance on new agriculture deals at MC11 reflects the continued significance for its small-scale farmers.

Hepburn added that it is unlikely that there could be an SSM outcome at the end of MC11 as signified by the WTO Committee on Agriculture Chair.

“At present, the chair of the WTO agriculture negotiations has told the membership that he doesn’t see the SSM as likely to be able to generate the consensus needed for an outcome at the 11th Ministerial Conference,” he said.

For his part, Roehlano M. Briones, Philippine Institute for Development Studies senior research fellow, said developed countries remain lukewarm to the creation of SSM as their exports would be the ones to be put at risk with such trade measure.

“That’s natural. They will probably find themselves on the receiving end of SSM complaints,” Briones told the BusinessMirror.

Briones said the Philippines could capitalize SSM to protect commodities largely produced by its local sectors such as rice, corn, poultry and hogs.

“They found the current framework lacking of punitive tariffs to impose and has stiff trigger mechanisms, so [creation of SSM] is really important for the Philippine side,” he said.

“From my perspective, really, this is to assure domestic stakeholders that they will not be disadvantaged by the onslaught of cheap foreign imports. It’s more like a political gambit to appease local stakeholders,” he added.

For Pork Producers Federation of the Philippines Inc. President Edwin G. Chen, the establishment of a working and effective special safeguard measure would ensure that local hog producers would not incur losses. Chen argued that the hog sector is prone to import surge as tariffs imposed on pork imports are low.

“That [SSM] is very important. In the past we have become dumping grounds [of cheap imports],” Chen told the BusinessMirror.

“For example, imports of [pork] offal,rinds and fats are being dumped here with very low tariff rates of 5 percent, 7 percent and 10 percent. And they are without [minimum access volume], so they have open volume,” Chen added.

Chen said pork import surges tend to depress the farm-gate price of locally produced pork, bringing them below the normal average price level.

MSMEs

ANOTHER priority of the Philippines in the MC11 is the development of micro, small and medium enterprises, or MSMEs.

“On MSMEs, our economy is comprised mainly [that’s 99.6 percent] of small enterprises that serve as the backbone and the prime mover of both domestic and regional growth. The decisions we make must therefore be effective and meaningful to them,” Lopez said in his speech.

“In this regard, the Philippines supports the establishment of a work program on MSMEs that would further enhance their ability to participate meaningfully in international trade whether directly or as part of global value chains. There must be more of competence and capacity building sharing,” Lopez added.

The trade chief said the work program should also look at the different characterizations of MSMEs at national levels to create the appropriate support and assistance for them.

“Let us work toward positive efforts such as aligning size definition to ensure that real MSMEs, particularly those in developing countries, secure a share in the growth in international trade commensurate with the needs of their development,” Lopez said.

In November, the Friends of MSMEs, a 28-nation group that includes the Philippines, asked the WTO to establish a program that would reduce trade costs and make it easier for more MSMEs to participate in and benefit from international trade.

The group submitted a draft ministerial decision on establishing a work program for MSMEs to the WTO General Council.

The draft ministerial decision, a copy of which was obtained by the BusinessMirror, has been circulated among WTO member-countries upon the request of the Friends of MSMEs.

The group hopes that it will get the nod of member-countries at MC11.

When the Philippine delegation to the 11th Ministerial Conference (MC11) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where more than 160 trade officials met to discuss the future of global trade, they came with one goal: protect the country’s small-scale farmers.

The Ministerial Conference, which is attended by trade ministers and other senior officials from the organization’s 164 members, is the highest decision-making body of the WTO. Under the “Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO,” the Ministerial Conference is set to meet at least once every two years.

Discussions during the Ministerial Conference revolve on issues that would pave the way for the growth of global trade. These issues may include talks on agricultural goods, export subsidies, farm productivity, technology, gender and anything under the sun that has something to do with trade.

But some global trade issues have remained contentious, such as negotiations on agriculture, including commitments on tariff cuts and protecting domestic farm sectors.

Safeguard

JUST before the Philippine delegation left for MC11, which started on December 11, President Duterte instructed them to get the best for Filipino farmers.

Of course [we will protect the farmers]. The President will always protect the farmers. But not to the point of straining the Philippines’ relationship with other countries,” Agriculture Secretary Emmanuel F. Piñol said in an interview during the opening of the 14th Regular Session of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission held in Pasay City on December 3.

We have to negotiate what is best for Philippine agriculture. I will just play a supporting role to the trade secretary because he is the head of the delegation,” added Piñol before heading for the airport that day. “But I assure the Filipino people that, as agriculture secretary, I will make sure that our interests are protected.

At the onset of the three-day MC11, the country’s trade negotiators have already rejected the efforts of rich countries to implement deeper tariff cuts on farm products. The Philippine trade negotiators were lukewarm to the idea of allowing developing countries to protect their domestic industries from harmful import surges.

In his speech delivered before fellow farm ministers, Piñol emphasized that the Philippines will not agree to new agricultural deals without passage of a concrete special safeguard mechanism (SSM) for developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs).

The Philippines once more wants to reiterate its firm decision that none of the priority of the WTO members provide sufficient political basis for us to support any concrete substantive outcome in this conference in the absence of a specific solution on SSM,” he said

This minimum requirement is even critical for the Philippines as members continue to evade the needed reforms in domestic support, especially phasing out trade-distorting support, including an interim commitment to limit supports at the product-specific level,” he added.

Push

PIÑOL urged WTO member-countries to act on the Philippine proposal to establishing SSM if they want to get the Southeast Asian country’s nod on any agricultural deal in the ongoing MC11.

Indeed, time is not on our side and members must not second guess our resolve if we are to make MC11 truly a success,” he said. “I therefore call on members with extreme urgency to act now and engage us on our proposal to have a specific and targeted solution on SSG [special safeguards] for some members on the basis of our proposal under ‘JOB AG 121’ and ‘JOB AG 123.’”

SSM is a trade measure that will allow developing countries to raise tariffs temporarily to deal with import surges or price falls, according to the WTO. It has become one of the most contentious trade issues within the WTO, especially between developed and developing countries.

In 2004 WTO member-countries agreed that SSM will be established for use by developing countries, as indicated in the so-called July Framework. In the 2005 Hong Kong Declaration, WTO developing country members will have the right to recourse to SSM based on import quantity and price triggers.

However, 13 years after the SSM was first floated within the WTO, a concrete framework on it has yet to be crafted. One of the most contentious issues concerning SSM is the “trigger level” and the rate of tariffs that will be imposed.

Under the current WTO Agreement on Agriculture, the Philippines has applied SSG to at least 118 farm commodities. SSG serves as contingency restrictions on imports taken temporarily to deal with special circumstances, such as a sudden surge in imports, according to the WTO.

Proposal

LAST month, the Philippines filed a proposal that sought to improve the current SSG measures within the WTO framework. This was after oppositions on the creation of an SSM were raised.

Raul Q. Montemayor, national business manager and program officer of the Federation of Free Farmers of the Philippines, told the BusinessMirror that since a lot of WTO member-countries derail talks on SSM, the country had to recourse to an alternative plan, which is to improve the current SSG system.

“What we presented is actually an alternative, which is to improve the existing SSG, particularly a price-based SSG,” he said. “It is actually an improved version of the current SSG in the hopes that they would agree on this.”

Montemayor, who is part of the Philippine delegation to MC11, explained that the country proposed the changes as the present SSG regime has stiff conditions making it ineffective to protect local farm sectors.

For one, the formula used to compute a country’s trigger price is still based on 1986-1988 prices, which is somehow inappropriate to present global prices, according to Montemayor.

“For example, for our rice imports, our trigger price is around P4 to P4.50 based on the 1986-1988 formula. But when you buy rice today in the international market, it costs around P15 per kilogram,” he said. “So, in that sense we cannot use the SSG.”

Under the Philippine proposal, the present 1986-1988 trigger price basis for SSG will be changed to a rolling three-year average import price.

Meaning, the trigger price, which is the price point wherein a country could invoke SSG, will depend on the prevailing import price in the recent three-year period.

Furthermore, the Philippines proposed to phase out the current complicated formula for additional tariffs when invoking SSG.

Under its proposal, once the SSG is invoked, affected countries could slap an additional tariff duty on the imported goods by as much as 90 percent of the price difference between the trigger price and imported price.

This is different from the current SSG regime wherein countries will apply additional tariffs for imports as a trade remedy.

“For example, your trigger price for poultry imports is P100 and an P80 chicken enters your border, so that will allow you to invoke SSG. So 90 percent of P20 is P18, then that will be your additional tariff,” Montemayor said.

“You will not set a tariff value in comparison to your trigger price. And this proposed SSG change applies per shipment, because there could be shipments that do not go below trigger price,” Montemayor added.

‘High time’

DURING his speech at the plenary session, Trade Secretary Ramon M. Lopez said inequities in agricultural trade continue to exist as few WTO member-countries maintain their large subsidies on farm products.

“It is high time that members made bold contributions today, once and for all, to address these gross imbalances and inequities in agriculture,” Lopez, who heads the Philippine delegation to MC11, said. “I therefore call on members to substantially reduce, toward elimination, trade-distorting subsidies by phasing out AMS [aggregate measurement of support] and limit supports at the product-specific level.”

The Trade Secretary pointed out that it is high time that an effective SSM be created at WTO as farm sectors of developing countries and LDCs have been damaged by highly subsidized exports for more than a decade now.

“Developing countries and LDCs must also be provided with an accessible and effective trade remedy tool, through the establishment of a special safeguard mechanism [SSM] that can protect their small and subsistence farmers from import surges and price depressions and shield them from subsidized exports,” he said. “After more than a decade of negotiations for SSM and ministers’ reaffirmation of our political commitment, developing countries and LDCs cannot get back home empty-handed once more.”

In a ministerial communiqué, the Group of 33 (G-33), which includes the Philippines, said the establishment of an SSM remains as the priority of the group to safeguard their food security, livelihood security and rural development interests.

“We wish also to reiterate that the Nairobi Ministerial Decision on SSM has strengthened the mandate in the July Framework and the Hong Kong Ministerial Declaration and reaffirms that developing members shall have recourse to both a price-based and volume-based SSM,” G-33 said in the document dated December 10.

“Members shall be engaged constructively and focus the discussion on outstanding issues and refrain from making any linkage with other issues, with a view to find a pro-development and balanced SSM, which is accessible and effective in addressing the impact of import surges and price depressions caused by short-term and cyclical volatilities,” the group added.

Opposition

FOR his part, Montemayor said the establishment of an SSM is a must in the current global trade regime as small-scale farmers remain at risk from highly subsidized imported goods.

“This is our trade remedy and we need this at a time wherein all our tariffs are low. So there’s more tendency for imports to come in and that’s why we need remedies like SSM,” he said.

However, talks on the establishment of SSM in Geneva, Switzerland, before going to Argentina have been stalled as WTO member-countries expressed divergent views on the trade remedy, with most nations showing disinterest to discuss the issue, according to a Geneva-based trade official.

Jonathan Hepburn, agriculture senior program manager at Geneva-based International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, said the passage of an effective and concrete SSM at the WTO has been delayed due to changes in priorities and interests of member-countries throughout the years.

“The negotiating dynamic at the WTO has evolved significantly since the Doha Round talks were launched in 2001—partly because government policies and international markets have changed, and partly because talks on trade have moved ahead in other fora, such as through bilateral and regional talks,” Hepburn told the BusinessMirror.

“Today, a number of exporting countries say they are only willing to pursue talks on a special safeguard mechanism as part of a broader negotiation on market access—including both developed and developing country exporters,” he added.

Hepburn noted that the Philippines’ negotiating stance on new agriculture deals at MC11 reflects the continued significance for its small-scale farmers.

Hepburn added that it is unlikely that there could be an SSM outcome at the end of MC11 as signified by the WTO Committee on Agriculture Chair.

“At present, the chair of the WTO agriculture negotiations has told the membership that he doesn’t see the SSM as likely to be able to generate the consensus needed for an outcome at the 11th Ministerial Conference,” he said.

For his part, Roehlano M. Briones, Philippine Institute for Development Studies senior research fellow, said developed countries remain lukewarm to the creation of SSM as their exports would be the ones to be put at risk with such trade measure.

“That’s natural. They will probably find themselves on the receiving end of SSM complaints,” Briones told the BusinessMirror.

Briones said the Philippines could capitalize SSM to protect commodities largely produced by its local sectors such as rice, corn, poultry and hogs.

“They found the current framework lacking of punitive tariffs to impose and has stiff trigger mechanisms, so [creation of SSM] is really important for the Philippine side,” he said.

“From my perspective, really, this is to assure domestic stakeholders that they will not be disadvantaged by the onslaught of cheap foreign imports. It’s more like a political gambit to appease local stakeholders,” he added.

For Pork Producers Federation of the Philippines Inc. President Edwin G. Chen, the establishment of a working and effective special safeguard measure would ensure that local hog producers would not incur losses. Chen argued that the hog sector is prone to import surge as tariffs imposed on pork imports are low.

“That [SSM] is very important. In the past we have become dumping grounds [of cheap imports],” Chen told the BusinessMirror.

“For example, imports of [pork] offal,rinds and fats are being dumped here with very low tariff rates of 5 percent, 7 percent and 10 percent. And they are without [minimum access volume], so they have open volume,” Chen added.

Chen said pork import surges tend to depress the farm-gate price of locally produced pork, bringing them below the normal average price level.

MSMEs

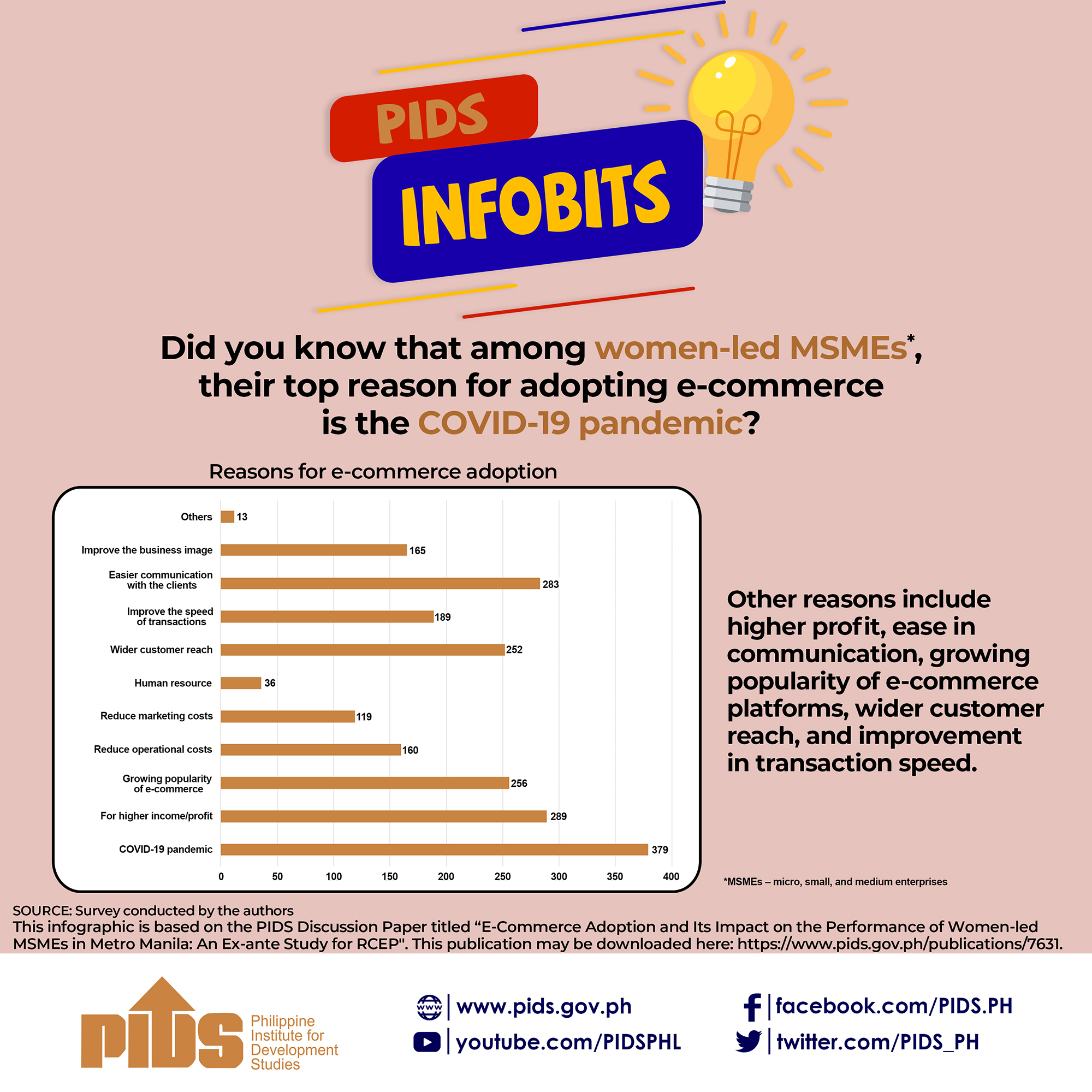

ANOTHER priority of the Philippines in the MC11 is the development of micro, small and medium enterprises, or MSMEs.

“On MSMEs, our economy is comprised mainly [that’s 99.6 percent] of small enterprises that serve as the backbone and the prime mover of both domestic and regional growth. The decisions we make must therefore be effective and meaningful to them,” Lopez said in his speech.

“In this regard, the Philippines supports the establishment of a work program on MSMEs that would further enhance their ability to participate meaningfully in international trade whether directly or as part of global value chains. There must be more of competence and capacity building sharing,” Lopez added.

The trade chief said the work program should also look at the different characterizations of MSMEs at national levels to create the appropriate support and assistance for them.

“Let us work toward positive efforts such as aligning size definition to ensure that real MSMEs, particularly those in developing countries, secure a share in the growth in international trade commensurate with the needs of their development,” Lopez said.

In November, the Friends of MSMEs, a 28-nation group that includes the Philippines, asked the WTO to establish a program that would reduce trade costs and make it easier for more MSMEs to participate in and benefit from international trade.

The group submitted a draft ministerial decision on establishing a work program for MSMEs to the WTO General Council.

The draft ministerial decision, a copy of which was obtained by the BusinessMirror, has been circulated among WTO member-countries upon the request of the Friends of MSMEs.

The group hopes that it will get the nod of member-countries at MC11.

“Costs related to foreign trade operations represent a significant burden for MSMEs interested in participating in international trade,” it read.

Once the draft ministerial decision is adopted by WTO member-countries at MC11, a work program addressing the issues surrounding the participation of MSMEs in global trade shall be established.

Among the issues to be tackled by the program is the improvement of access to information on trade requirements, regulations and markets for MSMEs. It will also address the ways to promote a more “predictable” regulatory environment for MSMEs.

Measures that contribute to reducing trade costs for MSMEs in areas, such as trade facilitation, shipping and logistics, and procedures and requirements related to origin will be identified.

The draft ministerial decision indicated that access to trade finance for MSMEs, including those through cooperation with other multilateral institutions, will be promoted

The work program must identify MSMEs’ issues that could be addressed in WTO Trade Policy reports and consider how they could benefit from technical assistance and capacity-building initiatives

“The discussions under the work program shall favor horizontal and nondiscriminatory solutions, which are likely to yield benefits for the participation of MSMEs in international trade, taking into account the specific needs of developing countries and least-developed countries,” the draft ministerial decision read.

Once the draft ministerial decision is adopted by WTO member-countries at MC11, a work program addressing the issues surrounding the participation of MSMEs in global trade shall be established.

Among the issues to be tackled by the program is the improvement of access to information on trade requirements, regulations and markets for MSMEs. It will also address the ways to promote a more “predictable” regulatory environment for MSMEs.

Measures that contribute to reducing trade costs for MSMEs in areas, such as trade facilitation, shipping and logistics, and procedures and requirements related to origin will be identified.

The draft ministerial decision indicated that access to trade finance for MSMEs, including those through cooperation with other multilateral institutions, will be promoted

The work program must identify MSMEs’ issues that could be addressed in WTO Trade Policy reports and consider how they could benefit from technical assistance and capacity-building initiatives

“The discussions under the work program shall favor horizontal and nondiscriminatory solutions, which are likely to yield benefits for the participation of MSMEs in international trade, taking into account the specific needs of developing countries and least-developed countries,” the draft ministerial decision read.