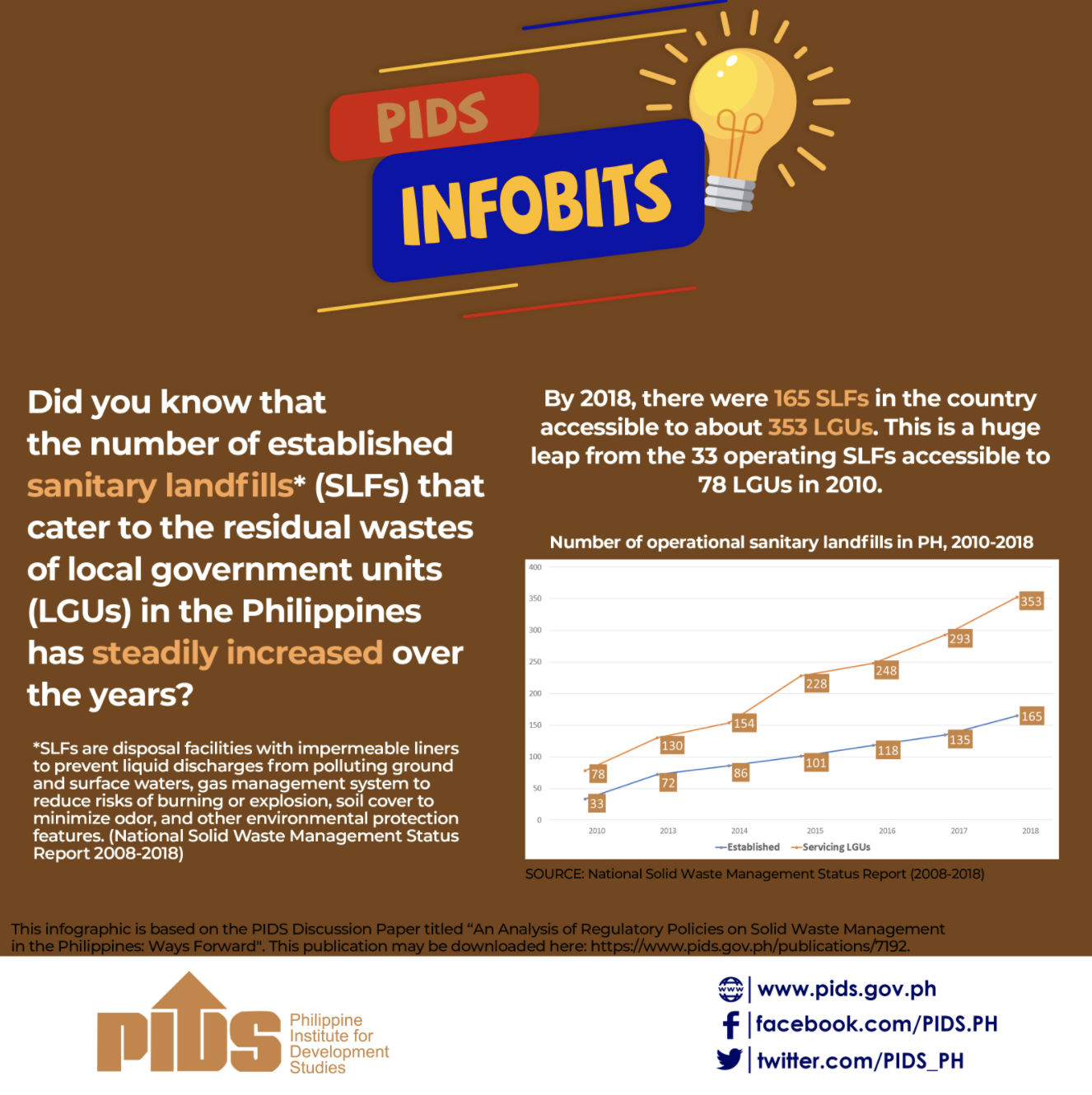

The country is still grappling with solid waste management issues despite the implementation of the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 or Republic Act 9003 for almost two decades now.

This, according to a discussion paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

PIDS Senior Research Fellow Sonny Domingo and PIDS Research Analyst II Arvie Joy Manejar, authors of the study, said that if RA 9003 has been properly implemented, it would have “conveniently and strategically allowed the imposition of systematic and structured remedies” that would have addressed the country’s problem on solid waste management.

For 2020, they noted an estimated total volume of 17 million metric tons of waste, a third of which would come from Metro Manila.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation with the surge of waste materials from the widespread use of disposable masks, shields, and personal protective equipment/gears, and other medical/healthcare supplies at both households and hospitals.

For instance, the San Lazaro hospital in Manila released around 29,000 kilograms of healthcare wastes between March and June last year.

Under RA 9003, local government units (LGUs) serve as lead implementers of the law and are tasked to establish the blueprint for national and subnational plans and initiatives on waste management. This legislation complements the devolution of solid waste management to LGUs as mandated by the Local Government Code of 1991.

Domingo and Manejar pointed out that the “overly simplistic transfer of responsibility to local government units…have resulted to two decades of mediocre policy grounding.” This is manifested, they said, in many issues, including the presence of illegal dumpsites, unabated waste generation, suboptimal material recovery, lack of investment in technology and facility, and the weak participation of both private and public in solid waste management.

Despite these challenges, the study found some best practices at the local level such as the “legal waste facility transition of the Payatas dumpsite in Quezon City and the organization of its informal economy; the clustering of waste management service of Teresa, Rizal, its province-wide incentive mechanism and partnership with construction companies, and the market linkages for revenue generation; and the strong LGU-CSO partnership in San Fernando, Pampanga”.

The study also presented some ways forward to improve solid waste management in the country.

One is for the national government to play an active role in designing and financing sanitary landfills and to promote a ‘clustering approach’ among adjacent LGUs because not all LGUs can host the establishment of engineered facilities.

Another is to augment the budget of LGUs for the establishment of waste facilities through other sources such as national to local transfers, aggregate arrangement between and among LGUs, and public-private sector arrangements.

The study also recommended reviewing “vertical institutional alignments” to strengthen the coordination between the national and local levels. Particularly, it urged the central government to go beyond its oversight functions in policy grounding and for the provinces to integrate their plans and programs with those of their covered cities and municipalities.

Lastly, it highlighted the need to provide relevant capacity-building interventions for communities and to strengthen information, education, and communication campaigns on waste reduction, segregation, reuse, and recycling at the local level. ###

This article is based on the PIDS discussion paper titled “An Analysis of Regulatory Policies on Solid Waste Management in the Philippines: Ways Forward”.

This, according to a discussion paper published by state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

PIDS Senior Research Fellow Sonny Domingo and PIDS Research Analyst II Arvie Joy Manejar, authors of the study, said that if RA 9003 has been properly implemented, it would have “conveniently and strategically allowed the imposition of systematic and structured remedies” that would have addressed the country’s problem on solid waste management.

For 2020, they noted an estimated total volume of 17 million metric tons of waste, a third of which would come from Metro Manila.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation with the surge of waste materials from the widespread use of disposable masks, shields, and personal protective equipment/gears, and other medical/healthcare supplies at both households and hospitals.

For instance, the San Lazaro hospital in Manila released around 29,000 kilograms of healthcare wastes between March and June last year.

Under RA 9003, local government units (LGUs) serve as lead implementers of the law and are tasked to establish the blueprint for national and subnational plans and initiatives on waste management. This legislation complements the devolution of solid waste management to LGUs as mandated by the Local Government Code of 1991.

Domingo and Manejar pointed out that the “overly simplistic transfer of responsibility to local government units…have resulted to two decades of mediocre policy grounding.” This is manifested, they said, in many issues, including the presence of illegal dumpsites, unabated waste generation, suboptimal material recovery, lack of investment in technology and facility, and the weak participation of both private and public in solid waste management.

Despite these challenges, the study found some best practices at the local level such as the “legal waste facility transition of the Payatas dumpsite in Quezon City and the organization of its informal economy; the clustering of waste management service of Teresa, Rizal, its province-wide incentive mechanism and partnership with construction companies, and the market linkages for revenue generation; and the strong LGU-CSO partnership in San Fernando, Pampanga”.

The study also presented some ways forward to improve solid waste management in the country.

One is for the national government to play an active role in designing and financing sanitary landfills and to promote a ‘clustering approach’ among adjacent LGUs because not all LGUs can host the establishment of engineered facilities.

Another is to augment the budget of LGUs for the establishment of waste facilities through other sources such as national to local transfers, aggregate arrangement between and among LGUs, and public-private sector arrangements.

The study also recommended reviewing “vertical institutional alignments” to strengthen the coordination between the national and local levels. Particularly, it urged the central government to go beyond its oversight functions in policy grounding and for the provinces to integrate their plans and programs with those of their covered cities and municipalities.

Lastly, it highlighted the need to provide relevant capacity-building interventions for communities and to strengthen information, education, and communication campaigns on waste reduction, segregation, reuse, and recycling at the local level. ###

This article is based on the PIDS discussion paper titled “An Analysis of Regulatory Policies on Solid Waste Management in the Philippines: Ways Forward”.