As such, the department said it is critical for the country to secure preferential access to these value chains.

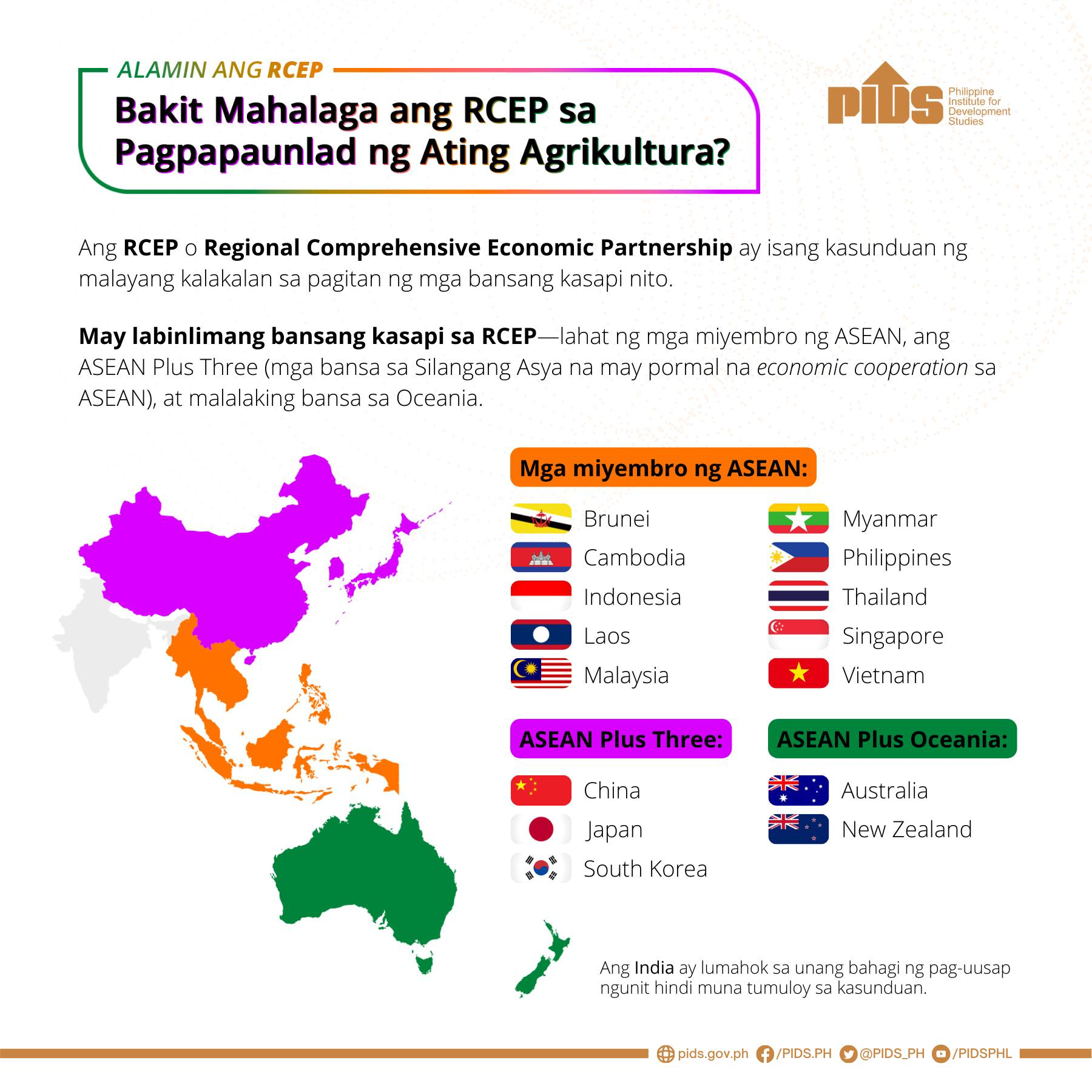

Dr. Francis Quimba, economist from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), said nonparticipation to RCEP will cause the Philippines to miss out on this opportunity to facilitate the much-needed economic growth and recovery.

He reiterated that delayed or non-participation to RCEP would lead to a 0.26-percent decline in real GDP of the Philippines.

“Economies that fail to ratify the agreement (when the rest of the countries do) will be adversely affected. The Philippines and Vietnam are among the countries that have positive export growths once the RCEP is in effect, and much of the growth is coming from newproduct margin where innovations stem,” said Dr. Quimba.

Citing his initial estimates, Quimba said that while East Asian countries stand to benefit the most in terms of increase in exports as RCEP will be the first FTA among the three, the Philippines and Vietnam will gain the most in terms of real GDP due to lower trade costs and higher factory gate prices.

For his part, Dr. Caesar Cororaton, a Research Fellow at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (USA) and a Visiting Scholar at the De La Salle University (DLSU), said RCEP is estimated to improve the country’s trade balance by as much as $128.2 million, increase overall welfare by $541.2 million, contribute to a 1.93- percent real GDP growth, and lower poverty incidence by 3.62 percent in 2031.

A study released by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) recognized RCEP’S strong potential to mold regional trade and investment patterns well into the future and to influence the direction of global economic cooperation at a challenging time. RCEP’S effects on the region’s trade will also significantly deepen regional production networks and raise productivity. At the sectoral level, exports and imports of nondurable and durable manufactures will experience the most growth.

Some stakeholders, however, pointed out that the ADB study indicates marginal gains for the Philippines, with the country only seeing an incremental increase in real income of $3 billion by 2030 (or 0.39-percent growth) compared to other RPCS such as China, Japan, and Korea.

Still, DTI’S Lopez said it is understandable that East Asian countries see the largest increase in incomes as this will be the first time that these three countries will have an FTA among each other.

“Prior to RCEP, there had been no FTA between China, Japan, and Korea, which means there is no pre-existing preferential treatment on traded goods among them, and MFN rates are applied. The same can also be said with trade in services and investment where these countries do not accord special treatment to services and investments coming from the other two countries,” said Lopez.

During the conduct of public hearings by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (CRF), the DTI said questions were raised by stakeholders on the impact of the RCEP Agreement on the Philippine economy, particularly in the context of the economic slowdown due to the pandemic, and the worsening trade balance of the Philippines.

The agency added that stakeholders also had concerns that the tariff liberalization that come with the RCEP Agreement would cripple the country’s ability to address the Covid-19 pandemic due to lower tariff revenues, and force local industries out of business with cheaper imported goods.

The DTI said the primary basis for these concerns is the study by Banga et al., published by Boston University, showing tariff liberalization under RCEP will negatively impact the balance of trade (BOT) of Asean countries.

It added that the balance of trade (BOT) of the region will deteriorate by 6 percent annually, primarily due to an increase in imports and trade diversion within the RCEP group towards more efficient exporters. For the Philippines, the study finds that exports are estimated to decrease by 0.2 percent while imports will increase by 0.2 percent, causing a decrease in the country’s trade balance by 1.1 percent.

While the figures presented by Banga et al. indicate a negative outcome for Asean’s trade balance post-rcep, the agency said it should be noted that the model used in the study is limited in scope as the same only takes into consideration changes in tariff rates and excludes other factors that may affect the country’s trade performance.