The signing of the rice tariffication bill into law in February (RA 11203) essentially triggers further liberalization in the importation of rice, in turn prompting significant structural changes in our food supply. By removing quantitative restrictions (QR) and imposing tariffs on rice imports instead, AND setting these tariffs at a level that allows slightly more importation, the additional supply in the market is projected to decrease rice prices by P2 to P7 per kilo based on estimates by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies. Government estimates suggest that tariffication will also bring in up to P28 billion in government revenues, which in turn could be allocated to support the rice industry.

An additional study by Dr. Ramon Clarete of University of the Philippines suggests that considering an exchange rate of P54 to 1 US dollar, a 35 percent tariff rate, and 10 percent marketing cost, the price of well-milled rice could be brought down from P39 to P31 per kilo with rice tariffication. As the weight of rice is at around 10 percent in the consumer price index (CPI), this translates to a decrease in inflation by 2.5 percentage points, and even twice that of the poor’s CPI.

This is the reform that should have helped cushion the impact of TRAIN1 – better late than never.

If rice tariffication is well implemented and market players (e.g. importers and local retailers) are well regulated, this reform is expected to benefit consumers – providing a boost to their real incomes thanks to lower rice prices. At least one estimate suggests that up to 3.8 million Filipinos could be lifted out of hunger due to this reform.

But what about rice farmers? From 2000 to 2017, a Philippine Institute for Development Studies study noted that the agriculture sector has slowed down from 3.2 to 1.4 percent, the weakest among economic sub-sectors. Although PIDS attributed this to the lack of spending and infrastructure allocated to science and technology in the country, the more important question is, how do we transform our institutions in combination with continuous upgrade in technologies?

GOVERNANCE IS KEY

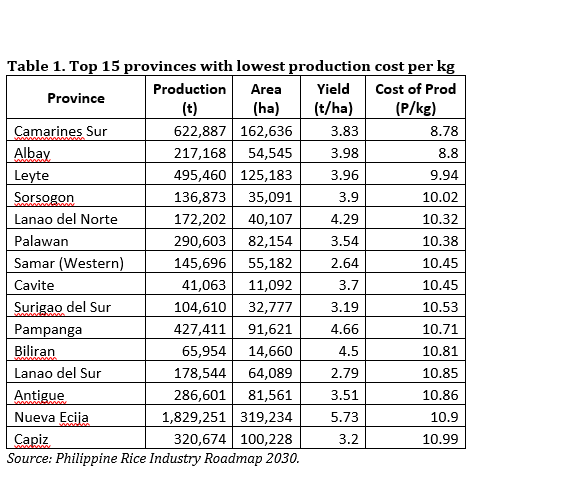

While estimates vary, there could be up to 3 million rice farmers in the country, and their range of competitiveness in producing rice varies across regions. The Rice Industry Roadmap identifies 57 key provinces that are in the government’s priority list to assist in terms of irrigation, provision of high-quality seeds, mechanization, market access, and other support strategies. Table 1 lists some of the most competitive provinces in terms of rice production (measured by indicators such as cost of production per kilogram, and yield (tons per hectare).

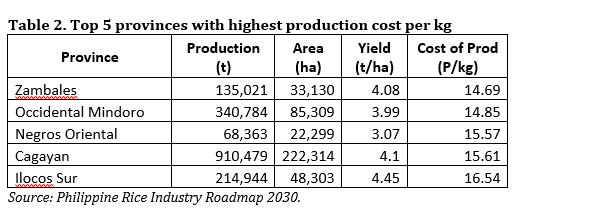

>Provinces like Nueva Ecija and Pampanga are actually competitive (notably in terms of yield and scale). Rice tariffication (and the subsequent increase in rice importation) will likely intensify competition notably for rice farmers in provinces like Occidental Mindoro and Negros Oriental (see Table 2). It is likely that in these provinces, some farmers may need safety nets, or perhaps financing mechanisms to diversify into other crops (or away from monocrop rice farming and into organic rice farming).

In order to utilize the full benefits of stronger food security, several key governance reforms will be needed. A few are worth noting here. First, and foremost, the schizophrenic management of the National Food Authority has been one of the banes of food security in the country. In recent years, many of its importation decisions have been mistimed. This agency’s management has also been racked with governance challenges and corruption allegations. In this last decade, rice prices spiked at least 3 times—first during the infamous international food price crisis in 2008-2009, a second time during the mishandling of rice stocks under the Alcala-led Department of Agriculture in 2013, and now finally a third time under the Piñol-led DA. On all three occasions, the National Food Authority was unable to temper the price shock, and analysts note that this is due to the NFA’s de facto monopoly over rice importation (or licensing of rice importers).

One of the key reforms under RA 11203 is to take rice import regulation out of the hands of the National Food Authority and empower instead the Bureau of Plant Industry which will now regulate import licensing through the Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary (SPS) measure. And in case you’re thinking that agency too will likely be captured by the corrupt, note that the permitting process will need to be completed within 7 days, otherwise triggering automatic approval. Together, this will help mitigate rent-seeking in the importation of rice.

Second, difficult structural adjustments will likely become necessary for our farmers and agricultural workers (extra farm hands whose livelihoods will be impacted by mechanization). Mechanization will likely trigger land agglomeration in order to achieve better returns. Some farmers may choose to diversify into new cash crops (e.g. organic farming) while still others may opt to retire from farming altogether. (Recall that the average age of farmers is 60 based on a 2017 survey by the Department of Agriculture.)

It will be critical to design effective financing mechanisms and safety nets that could assist farmers to transition successfully to a new—hopefully more productive agricultural equilibrium—characterized by stronger cooperatives, and more efficient land agglomeration combined with mechanization and technology and financing access.

Finally, in order to achieve stronger food production, Filipino farmers will need access to new technology, farm equipment and mechanization, as well as training and better market linkages. RA 11203 allocates at least P10 billion for the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) which is expected to help bolster the rice industry, providing financing for many of these investments. However, RA11203 does not provide for farmer participation in managing the allocation of (RCEF).

Following the troubles that our coconut farmers encountered with the coco levy fiasco and the lessons that we have supposedly learned from it, it is not surprising how many of our rice farmers feel that their livelihoods are at risk. Since RCEF is designed to be implemented by 4 government agencies (PhilMEC, PhilRICE, LandBank and TESDA), it is less apparent how farmers will be given a voice in how these funds are allocated. This is an area for improvement under the IRR for RA 11203.

P10 billion sounds like a large investment in our rice sector – but recall that we have spent many billions on agriculture already, yet food security has still remained elusive. In 2017 the Department of Agriculture had a budget allocation of P46 billion and in 2018, the budget reached almost P60 billion. Some legislators lobbied to increase it to beyond PhP120 billion in 2019.

Money is not the main issue. The governance of where and how it’s spent is.

FARMERS AS PARTNERS, NOT BENEFICIARIES

Long-term food security will need a whole-of-country approach in the agricultural sector, both across commodity sectors and institutions. To date, agriculture expenditure is only about 4.75 percent of the total National Expenditure Program annually. This is compared to 9 percent in Thailand and 11 percent in Indonesia. Furthermore, allocations do not necessarily flow to regions with the lowest productivity. And finally and perhaps most important, agricultural spending and investments are still hounded by inefficiency and corruption issues, based on longstanding evidence on this sector.

The long history of our farmers being left behind despite the country’s economic progress has created significant distrust with strategies to promote more economic openness. This is understandable given the failure to capacitate the agricultural sector to compete in the international arena. Rice tariffication— which is again a de facto form of trade liberalization—is an opportunity to break from this past.

Lifting the QR on rice breaks long-established corruption-prone structures, and it could serve as a prelude to a more comprehensive reform of the rice and agricultural sector writ large. And because their very livelihoods are again at stake, and they are expected to take risks to build a stronger agricultural sector, it is only fair (and probably more effective) that farmers should be given a stronger voice in this entire structural adjustment process.

As Ka Rene Cerilla of PAKISAMA reiterates, we should start looking at our farmers as partners, and not as beneficiaries.